The National Research Council (NRC) published ABRUPT IMPACTS OF CLIMATE CHANGE recently, downloadable from the National Academies Press website.

It’s the third NRC report to focus on abrupt climate change, the first being published in 2002. NRC members are drawn from the councils of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, and the Institute of Medicine.

The climate change issue is a profound problem in causal discovery and forecasting, to say the very least.

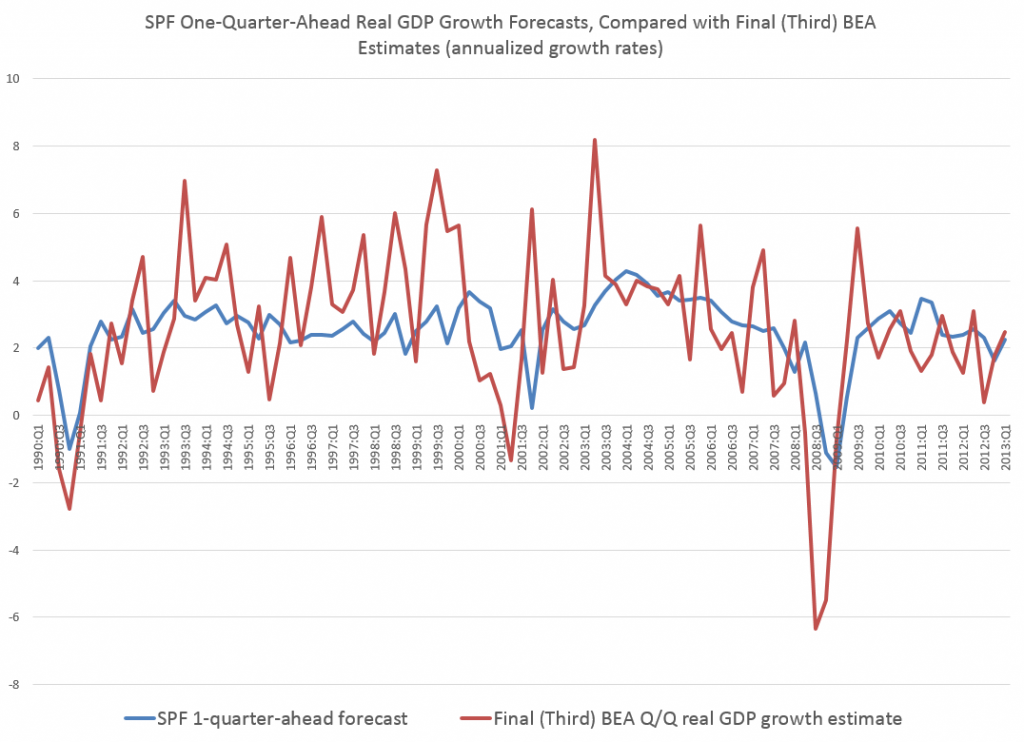

Before I highlight graphic and pictoral resources of the recent NRC report, let me note that Menzie Chin at Econbrowser posted recently on Economic Implications of Anthropogenic Climate Change and Extreme Weather. Chin focuses on the scientific consensus, presenting graphics illustrating the more or less relentless upward march of global average temperatures and estimates (by James Stock no less) of the man-made (anthropogenic) component.

The Econbrowser Comments section is usually interesting and revealing, and this time is no exception. Comments range from “climate change is a left-wing conspiracy” and arguments that “warmer would be better” to the more defensible thought that coming to grips with global climate change would probably mean restructuring our economic setup, its incentives, and so forth.

But I do think the main aspects of the climate change problem – is it real, what are its impacts, what can be done – are amenable to causal analysis at fairly deep levels.

To dispel ideological nonsense, current trends in energy use – growing globally at about 2 percent per annum over a long period – lead to the Earth becoming a small star within two thousand years, or less – generating the amount of energy radiated by the Sun. Of course, changes in energy use trends can be expected before then, when for example the average ambient temperature reaches the boiling point of water, and so forth. These types of calculations also can be made realistically about the proliferation of the automobile culture globally with respect to air pollution and, again, contributions to average temperature. Or one might simply consider the increase in the use of materials and energy for a global population of ten billion, up from today’s number of about 7 billion.

Highlights of the Recent NRC Report

It’s worth quoting the opening paragraph of the report summary –

Levels of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases in Earth’s atmosphere are exceeding levels recorded in the past millions of years, and thus climate is being forced beyond the range of the recent geological era. Lacking concerted action by the world’s nations, it is clear that the future climate will be warmer, sea levels will rise, global rainfall patterns will change, and ecosystems will be altered.

So because of growing CO2 (and other greenhouse gases), climate change is underway.

The question considered in ABRUPT IMPACTS OF CLIMATE CHANGE (AICH), however, is whether various thresholds will be crossed, whereby rapid, relatively discontinuous climate change occurs. Such abrupt changes – with radical shifts occurring over decades, rather than centuries – before. AICH thus cites,

..the end of the Younger Dryas, a period of cold climatic conditions and drought in the north that occurred about 12,000 years ago. Following a millennium-long cold period, the Younger Dryas abruptly terminated in a few decades or less and is associated with the extinction of 72 percent of the large-bodied mammals in North America.

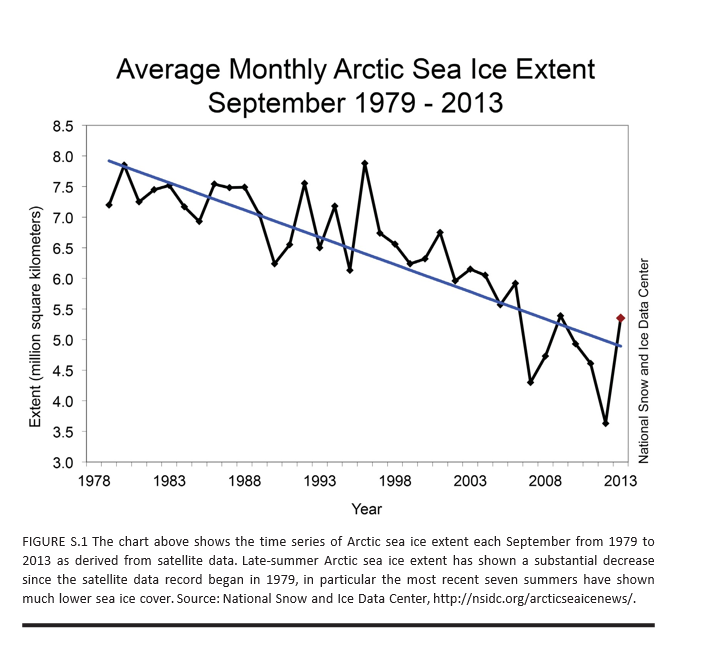

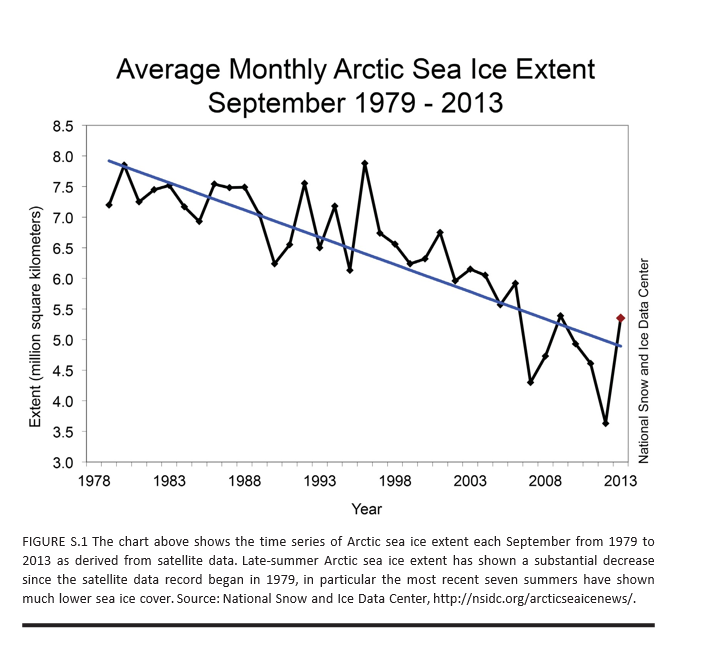

The main abrupt climate change noted in AICH is rapid decline of the Artic sea ice. AICH puts up a chart which is one of the clearest examples of a trend you can pull from environmental science, I would think.

AICH also puts species extinction front and center as a near-term and certain discontinuous effect of current trends.

Apart from melting of the Artic sea ice and species extinction, AICH lists destabilization of the Antarctic ice sheet as a nearer term possibility with dramatic consequences. Because a lot of this ice in the Antarctic is underwater, apparently, it is more at risk than, say, the Greenland ice sheet. Melting of either one (or both) of these ice sheets would raise sea levels tens of meters – an estimated 60 meters with melting of both.

Two other possibilities mentioned in previous NRC reports on abrupt climate change are discussed and evaluated as low probability developments until after 2100. These are stopping of the ocean currents that circulate water in the Atlantic, warming northern Europe, and release of methane from permafrost or deep ocean deposits.

The AMOC is the ocean circulation pattern that involves the northward flow of warm near-surface waters into the northern North Atlantic and Nordic Seas, and the south- ward flow at depth of the cold dense waters formed in those high latitude regions. This circulation pattern plays a critical role in the global transport of oceanic heat, salt, and carbon. Paleoclimate evidence of temperature and other changes recorded in North Atlantic Ocean sediments, Greenland ice cores and other archives suggest that the AMOC abruptly shut down and restarted in the past—possibly triggered by large pulses of glacial meltwater or gradual meltwater supplies crossing a threshold—raising questions about the potential for abrupt change in the future.

Despite these concerns, recent climate and Earth system model simulations indicate that the AMOC is currently stable in the face of likely perturbations, and that an abrupt change will not occur in this century. This is a robust result across many different models, and one that eases some of the concerns about future climate change.

With respect to the methane deposits in Siberia and elsewhere,

Large amounts of carbon are stored at high latitudes in potentially labile reservoirs such as permafrost soils and methane-containing ices called methane hydrate or clathrate, especially offshore in ocean marginal sediments. Owing to their sheer size, these carbon stocks have the potential to massively affect Earth’s climate should they somehow be released to the atmosphere. An abrupt release of methane is particularly worrisome because methane is many times more potent than carbon dioxide as a greenhouse gas over short time scales. Furthermore, methane is oxidized to carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, representing another carbon dioxide pathway from the biosphere to the atmosphere.

According to current scientific understanding, Arctic carbon stores are poised to play a significant amplifying role in the century-scale buildup of carbon dioxide and methane in the atmosphere, but are unlikely to do so abruptly, i.e., on a timescale of one or a few decades. Although comforting, this conclusion is based on immature science and sparse monitoring capabilities. Basic research is required to assess the long-term stability of currently frozen Arctic and sub-Arctic soil stocks, and of the possibility of increasing the release of methane gas bubbles from currently frozen marine and terrestrial sediments, as temperatures rise.

So some bad news and, I suppose, good news – more time to address what would certainly be completely catastrophic to the global economy and world population.

AICH has some neat graphics and pictoral exhibits.

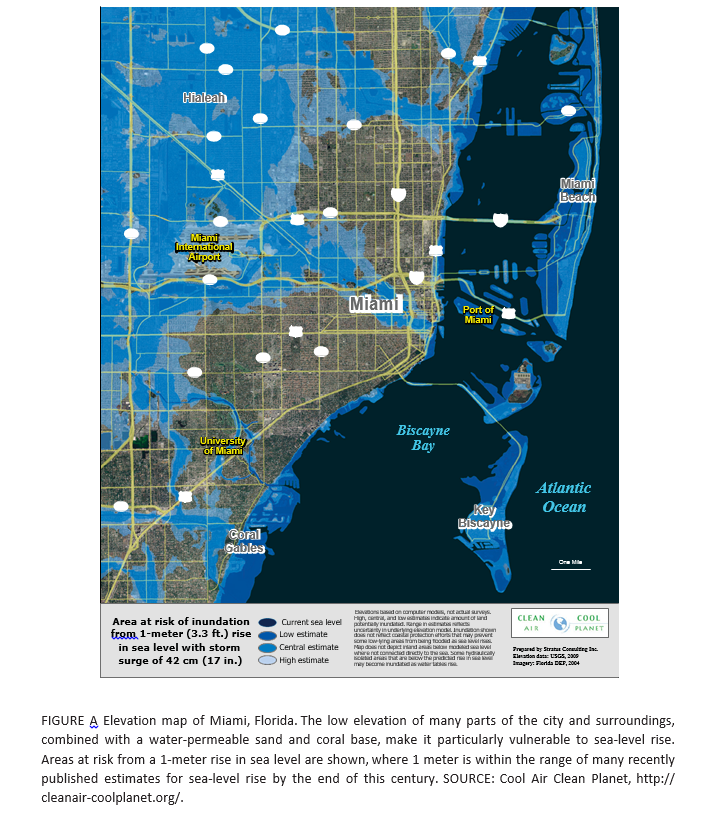

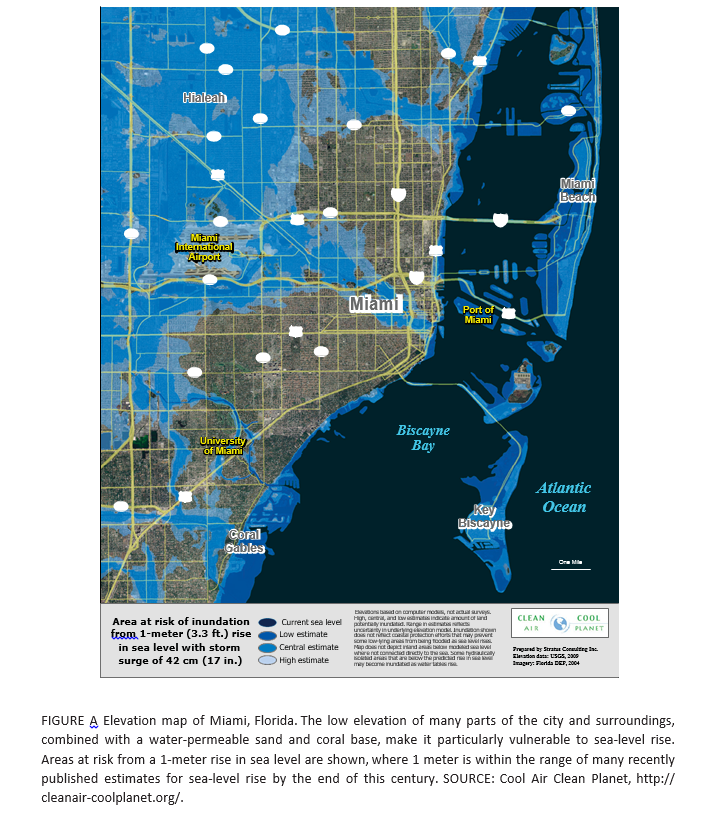

For example, Miami Florida will be largely underwater within a few decades, according to many standard forecasts of increases in sea level (click to enlarge).

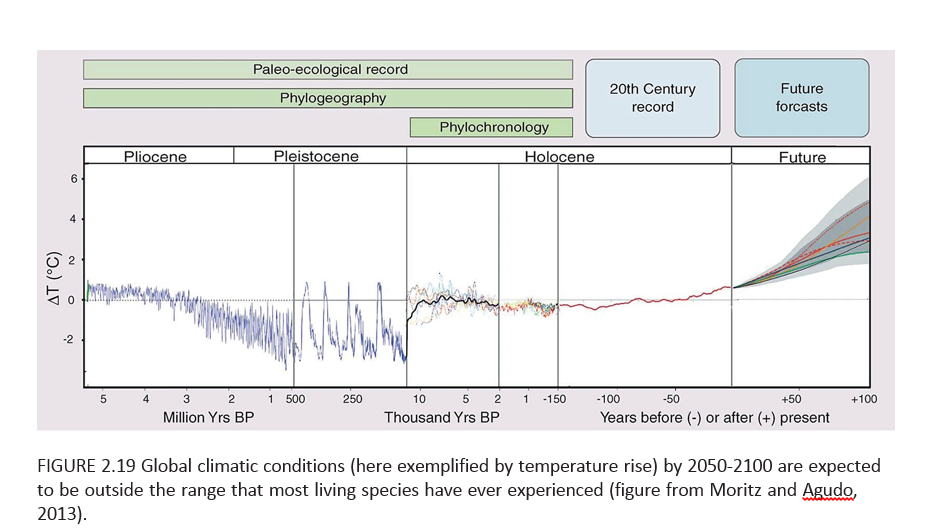

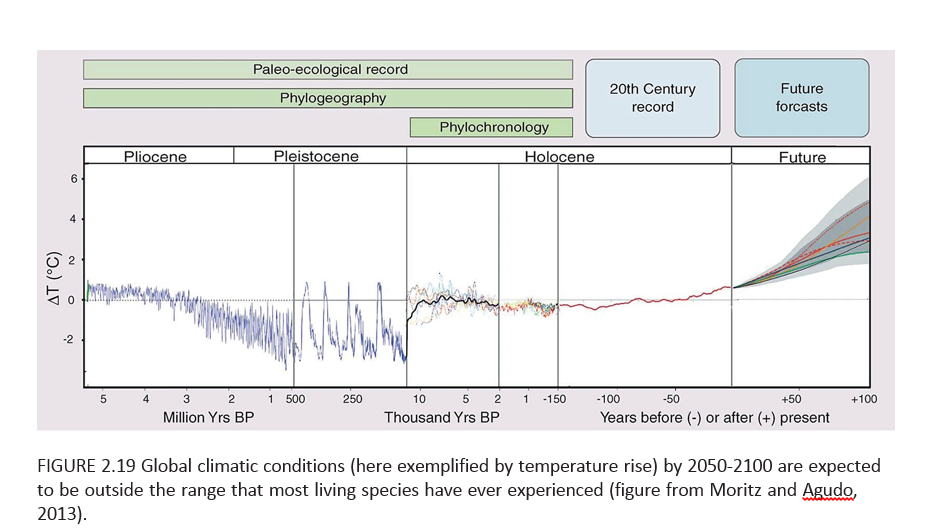

But perhaps most chilling of all (actually not a good metaphor here but you know what I mean) is a graphic I have not seen before, but which dovetails with my initial comments and observations of physicists.

This chart toward the end of the AICH report projects increase in global temperature beyond any past historic level (or prehistoric, for that matter) by the end of the century.

So, for sure, there will be species extinction in the near term, hopefully not including the human species just yet.

Economic Impacts

In closing, I do think the primary obstacle to a sober evaluation of climate change involves social and economic implications. The climate change deniers may be right – acknowledging and adequately planning for responses to climate change would involve significant changes in social control and probably economic organization.

Of course, the AICH adopts a more moderate perspective – let’s be sure and set up monitoring of all this, so we can be prepared.

Hopefully, that will happen to some degree.

But adopting a more pro-active stance seems unlikely, at least in the near term. There is a wholesale rush to bringing one to several trillion persons who are basically living in huts with dirt floors into “the modern world.” Their children are traveling to cities, where they will earn much higher incomes, probably, and send money back home. The urge to have a family is almost universal, almost a concomitant of healthy love of a man and a woman. Tradeoffs between economic growth and environmental quality are a tough sell, when there are millions of new consumers and workers to be incorporated into the global supply chain. The developed nations – where energy and pollution output ratios are much better – are not persuasive when they suggest a developing giant like India or China should tow the line, limit energy consumption, throttle back economic growth in order to have a cooler future for the planet. You already got yours Jack, and now you want to cut back? What about mine? As standards of living degrade in the developed world with slower growth there, and as the wealthy grab more power in the situation, garnering even more relative wealth, the political dialogue gets stuck, when it comes to making changes for the good of all.

I could continue, and probably will sometime, but it seems to me that from a longer term forecasting perspective darker scenarios could well be considered. I’m sure we will see quite a few of these. One of the primary ones would be a kind of devolution of the global economy – the sort of thing one might expect if air travel were less possible because of, say, a major uptick in volcanism, or huge droughts took hold in parts of Asia.

Again and again, I come back to the personal thought of local self-reliance. There has been a growth with global supply chains and various centralizations, mergers, and so forth toward de-skilling populations, pushing them into meaningless service sector jobs (fast food), and losing old knowledge about, say, canning fruits and vegetables, or simply growing your own food. This sort of thing has always been a sort of quirky alternative to life in the fast lane. But inasmuch as life in the fast lane involves too much energy use for too many people to pursue, I think decentralized alternatives for lifestyle deserve a serious second look.

Polar bear on ice flow at top from http://metro.co.uk/2010/03/03/polar-bears-cling-to-iceberg-as-climate-change-ruins-their-day-141656/