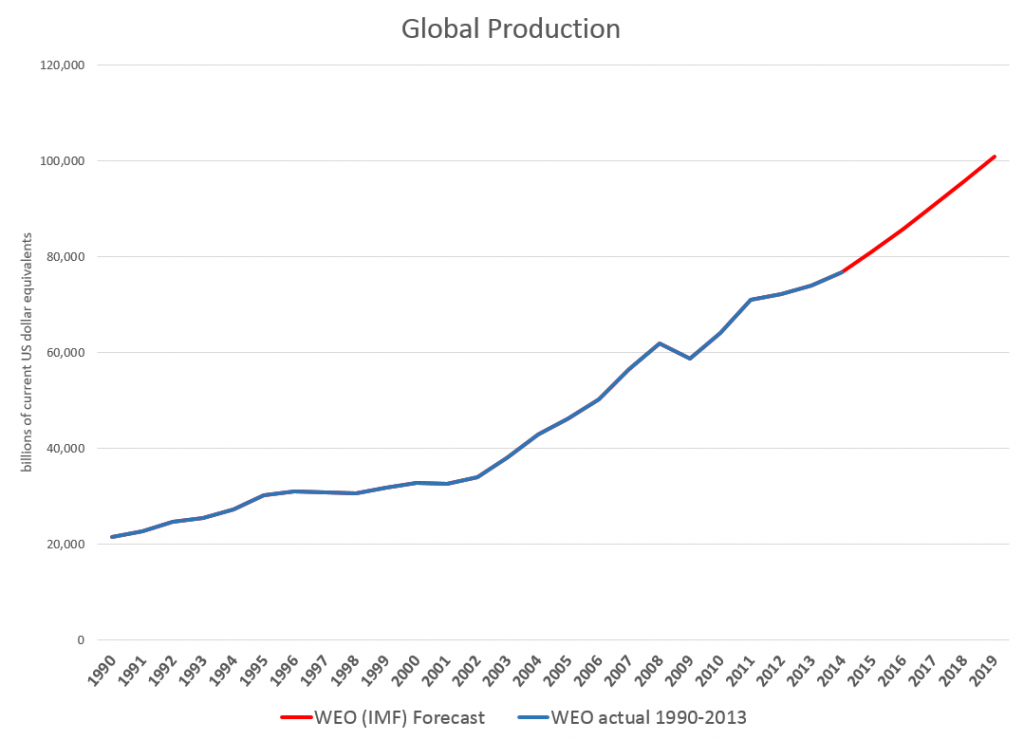

Larry Summers, former US Treasury Secretary and, earlier, President of Harvard delivered a curious speech at an IMF Economic Forum last year. After nice words about Stanley Fischer, currently Vice Chair of the Fed, Summers entertains the notion of negative interest rates to combat secular stagnation and restore balance between aggregate demand and supply at something like full employment.

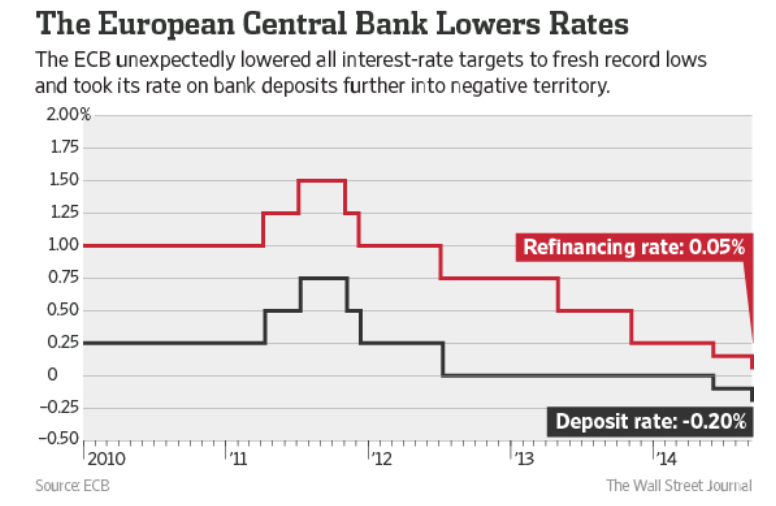

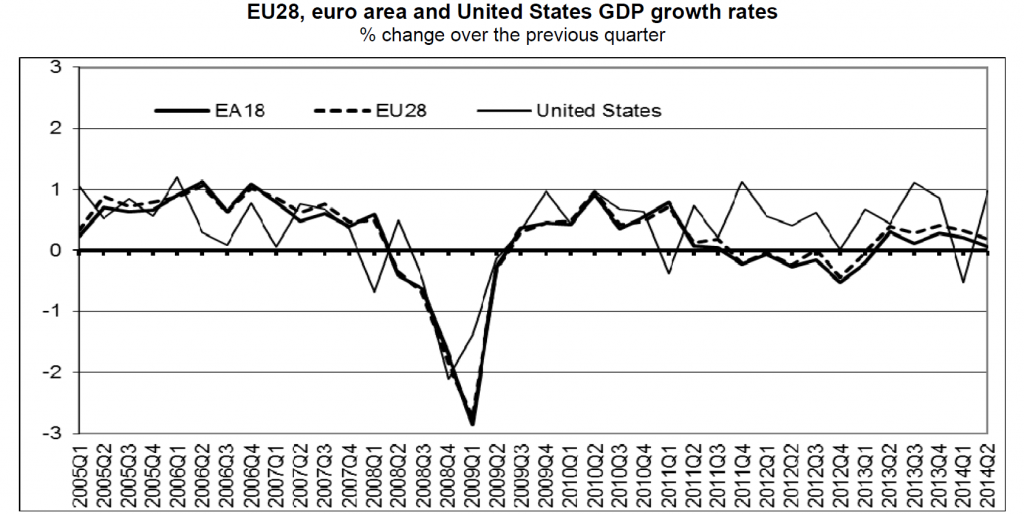

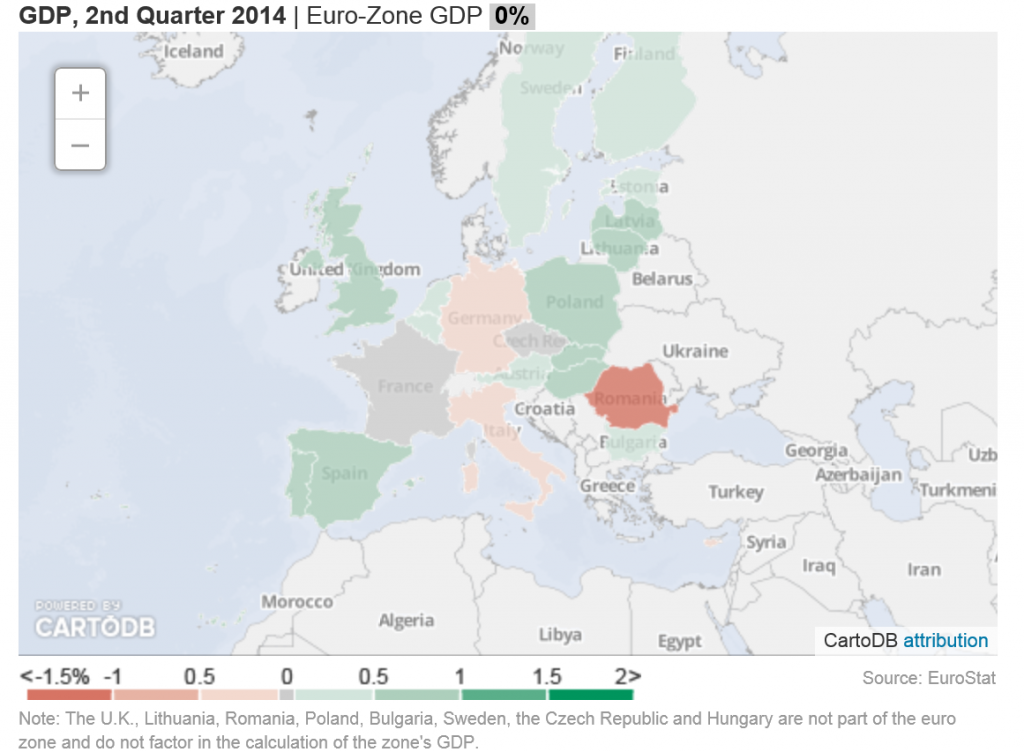

Fast forward to June 2014, when the European Central Bank (ECB) pushes the interest rate on deposits European banks hold in the ECB into negative territory. And on September 4, the ECB drops the deposit rates further to -0.2 percent, also reducing a refinancing rate to virtually zero.

The ECB discusses this on its website – Why Has the ECB Introduced a Negative interest Rate. After highlighting the ECB mandate to ensure price stability by aiming for an inflation rate of below but close to 2% over the medium term, the website observes euro area inflation is expected to remain considerably below 2% for a prolonged period.

This provides a rationale for lower interest rates, of which there are principally three under ECB control – a marginal lending facility for overnight lending to banks, the main refinancing operations and the deposit facility.

Note that the main refinancing rate is the rate at which banks can regularly borrow from the ECB while the deposit rate is the rate banks receive for funds parked at the central bank.

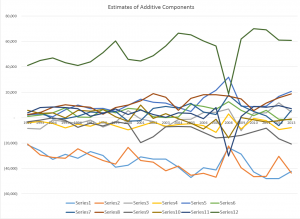

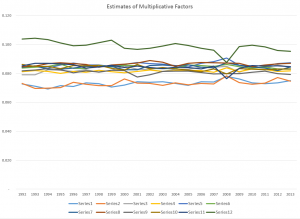

The ECB is adjusting interest rates under their control across the board, as suggested by the chart, but worries that to maintain a functioning money market in which commercial banks lend to each other, these rates cannot be too close to each other.

So, bottom line, the deposit rate was lowered to − 0.10 % in June to maintain this corridor, and then further as the refinancing rate was dropped to -.05 percent.

The hope is that lower refinancing rates will mean lower rates for customers for bank loans, while negative deposit rates will act as a disincentive for banks to simply park excess reserves in the ECB.

Nominal Versus Real Interest Rates and Bond Yields

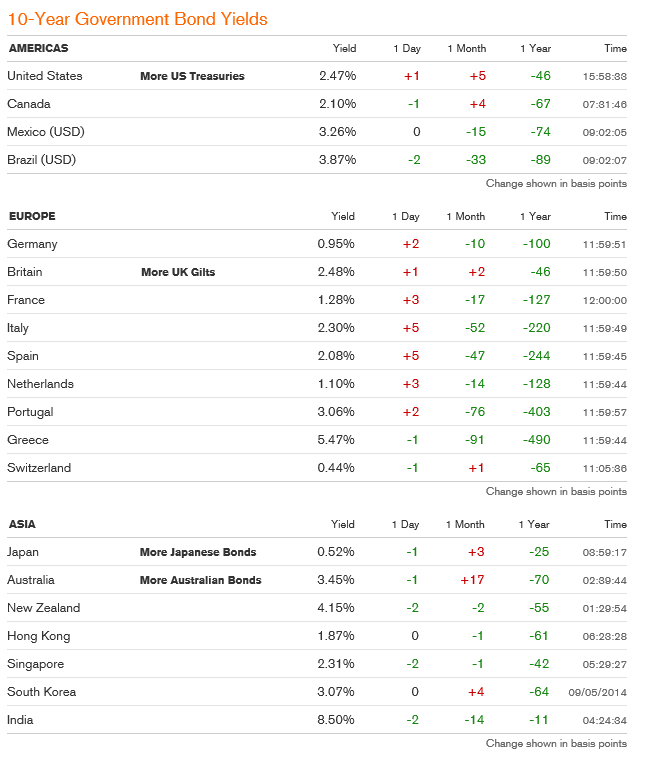

If you want to prep for, say, negative yields on two year Irish bonds, or issuance of various European bonds with negative yield, as well as the negative yields of a variety of US securities in recent years, after inflation, check out How Low Can You Go? Negative Interest Rates and Investors’ Flight to Safety.

An asset can generate a negative yield, on a conventional, rather than catastrophic basis, in a nominal or real, which is to say, inflation-adjusted, sense.

Some examples of negative real interest rates of yields –

The yield to maturity on the 5-year Treasury note has been below 2 percent since July 2010, and the yield to maturity on the 10-year Treasury note has been below 2 percent since May 2012. Yet, looking forward, the Federal Open Market Committee in January 2012 announced an inflation target of 2 percent—implying an anticipated negative real yield over the life of the securities. Investors, facing uncertainty, appear willing to pay the U.S. government—when measured in real, ex post inflation-adjusted dollars—for the privilege of owning Treasury securities.

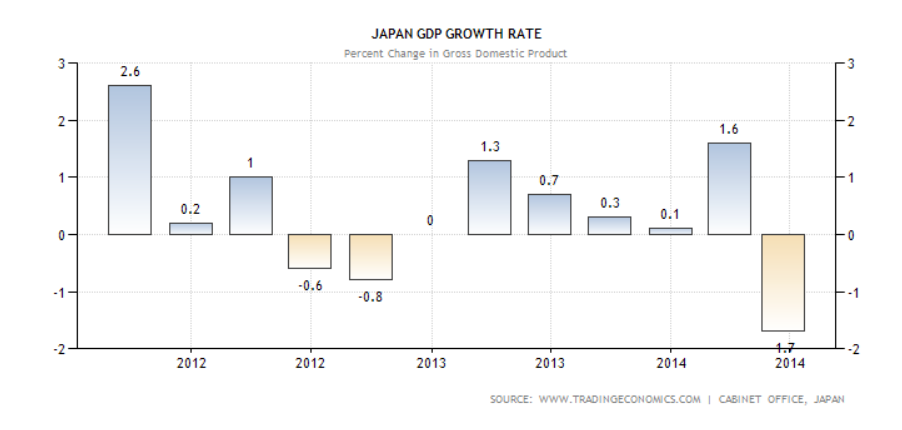

And the current government bond yield situation, from Bloomberg, shows important instances of negative yields, notably Germany and Japan – two of the largest global economies. Click to enlarge.

Where the ECB Goes From Here

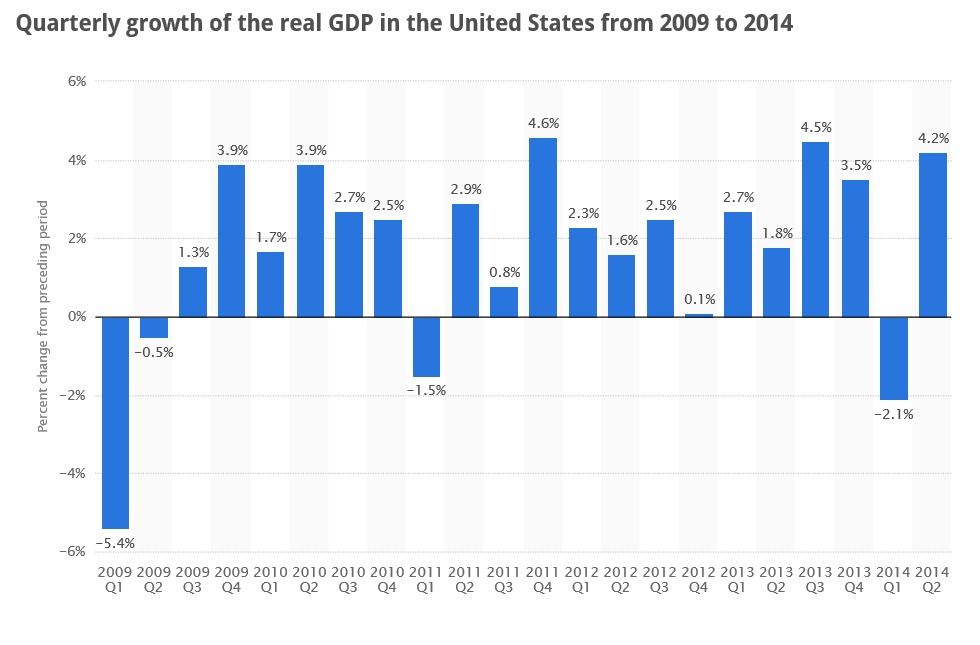

Mario Draghi, ECB head, gave a speech clearly stating monetary policy is not enough, at the recent Jackson Hole conference of central bankers. After this, the financial press was abuzz with the idea Draghi is moving toward the Japanese leader Abe’s formulation in which there are three weapons or arrows in the Japanese formulation– monetary policy, fiscal policy and structural reforms.

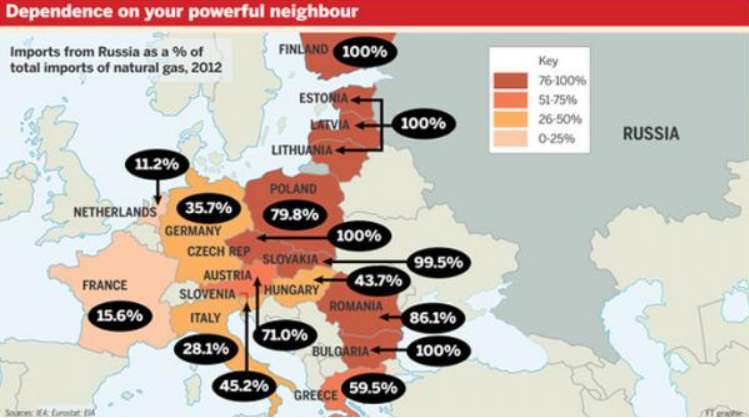

The problem, in the case of the Eurozone, is achieving political consensus for fiscal policies such as backing bonds for badly needed infrastructure development. German opposition seems to be sustained and powerful.

Because of the “political economy” factors , currency and banking problems in the Eurozone are probably more complicated and puzzling than many business executives and managers, looking for a take on the situation, would prefer.

A Thought Experiment

Before diving into this conceptually hazardous topic, though, I’d like to pose a puzzle for readers.

Can banks realistically “charge” negative interest rates to commercial customers?

I seem to have cooked up a spreadsheet where such loans could pay a rate of positive real return to banks, if the rate of deflation can be projected. In one variant, the bank collects a lending fee at the outset and then the interest rate for installments is negative.

The “save” for banks is that future deflation could inflate the real value of declining nominal installment payments, creating a present value of this stream of payments which is greater than the simple sum of such payments.

I’m not ready for primetime television with this, but it seems such a world encapsulates a very dour view of the future – one that may not be too far from the actual situation in Europe and Japan.

Money black hole at top from Conservative Read