Yesterday, I posted the latest Bloomberg top twenty US macroeconomic forecaster rankings, also noting whether this current crop made it into the top twenty in previous “competitions” for November 2010-November 2012 or November 2009-November 2011.

It turns out the Bloomberg top twenty is relatively stable. Seven names or teams on the 2014 list appear in both previous competitions. Seventeen made it into the top twenty at least twice in the past three years.

But who are these people and how can we learn about their forecasts on a real-time basis?

Well, as you might guess, this is a pretty exclusive club. Many are Chief Economists and company Directors in investment advisory organizations serving private clients. Several did a stint on the staff of the Federal Reserve earlier in their career. Their public interface is chiefly through TV interviews, especially Bloomberg TV, or other media coverage.

I found a couple of exceptions, however – Michael Carey and Russell Price.

Michael Carey and Crédit Agricole

Michael Carey is Chief Economist North America Crédit Agricole CIB. He ranked 14, 7, and 5, based on his average scores for his forecasts of the key indicators in these three consecutive competitions. He apparently is especially good on employment forecasts.

Carey is a lead author for a quarterly publication from Crédit Agricole called Prospects Macro.

The Summary for the current issue (1st Quarter 2014) caught my interest –

On the economic trend front, an imperfect normalisation seems to be getting underway. One may talk about a normalisation insofar as – unlike the two previous financial years – analysts have forecast a resumption of synchronous growth in the US, the Eurozone and China. US growth is forecast to rise from 1.8% in 2013 to 2.7%; Eurozone growth is slated to return to positive territory, improving from -0.4% to +1.0%; while Chinese growth is forecast to dip slightly, from 7.7% to 7.2%, which does not appear unwelcome nor requiring remedial measures. The imperfect character of the forecast normalisation quickly emerges when one looks at the growth predictions for 2015. In each of the three regions, growth is not gathering pace, or only very slightly. It is very difficult to defend the idea of a cyclical mechanism of self-sustaining economic acceleration. This observation seems to echo an ongoing academic debate: growth in industrialised countries seems destined to be weak in the years ahead. Partly, this is because structural growth drivers seem to be hampered (by demographics, debt and technology shocks), and partly because real interest rates seem too high and difficult to cut, with money-market rates that are already virtually at zero and low inflation, which is likely to last. For the markets, monetary policies can only be ‘reflationist’. Equities prices will rise until they come upagainst the overvaluation barrier and long-term rates will continue to climb, but without reaching levels justified by growth and inflation fundamentals.

I like that – an “imperfect normalization” (note the British spelling). A key sentence seems to be “It is very difficult to defend the idea of a cyclical mechanism of self-sustaining economic acceleration.”

So maybe the issue is 2015.

The discussion of emerging markets prospects is well-worth quoting also.

At 4.6% (and 4.2% excluding China), average growth in 2013 across all emerging countries seems likely to have been at its lowest since 2002, apart from the crisis year of 2009. Despite the forecast slowdown in China (7.2%, after 7.7%), the overall pace of growth for EMs is likely to pick up slightly in 2014 (to 4.8%, and 4.5% excluding China). The trend is likely to continue through 2015. This modest rebound, despite the poor growth figures expected from Brazil, is due to the slightly improved performance of a few other large emerging economies such as India, and above all Mexico, South Korea and some Central European countries. As regards the content of this growth, it is investment that should improve, on the strength of better growth prospects in the industrialised countries…

The growth differential with the industrialised countries has narrowed to around 3%, whereas it had stood at around 5% between 2003 and 2011…

This situation is unlikely to change radically in 2014. Emerging markets should continue to labour under two constraints. First off, the deterioration in current accounts has worsened as a result of fairly weak external demand, stagnating commodity prices, and domestic demand levels that are still sticky in many emerging countries…Commodity-exporting countries and most Asian exporters of manufactured goods are still generating surpluses, although these are shrinking. Conversely, large emerging countries such as India, Indonesia, Brazil, Turkey and South Africa are generating deficits that are in some cases reaching alarming proportions – especially in Turkey. These imbalances could restrict growth in 2014-15, either by encouraging governments to tighten monetary conditions or by limiting access to foreign financing.

Secondly, most emerging countries are now paying the price for their reluctance to embrace reform in the years of strong global growth prior to the great global financial crisis. This price is today reflected in falling potential growth levels in some emerging countries, whose weaknesses are now becoming increasingly clear. Examples are Russia and its addiction to commodities; Brazil and its lack of infrastructure, low savings rate and unruly inflation; India and its lack of infrastructure, weakening rate of investment and political dependence of the Federal state on the federated states. Unfortunately, the less favourable international situation (think rising interest rates) and local contexts (eg, elections in India and Brazil in 2014) make implementing significant reforms more difficult over the coming quarters. This is having a depressing effect on prospects for growth

I’m subscribing to notices of updates to this and other higher frequency reports from Crédit Agricole.

Russell Price and Ameriprise

Russell Price, younger than Michael Carey, was Number 7 on the current Bloomberg list of top US macro forecasters, ranking 16 the previous year. He has his own monthly publication with Ameriprise called Economic Perspectives.

The current issue dated January 28, 2014 is more US-centric, and projects a “modest pace of recovery” for the “next 3 to 5 years.” Still, the current issue warns that analyst projections of company profits are probably “overly optimistic.”

I need to read one or two more of the issues to properly evaluate, but Economic Perspectives is definitely a cut above the average riff on macroeconomic prospects.

Another Way To Tap Into Forecasts of the Top Bloomberg Forecasters

The Wall Street Journal’s Market Watch is another way to tap into forecasts from names and teams on the top Bloomberg lists.

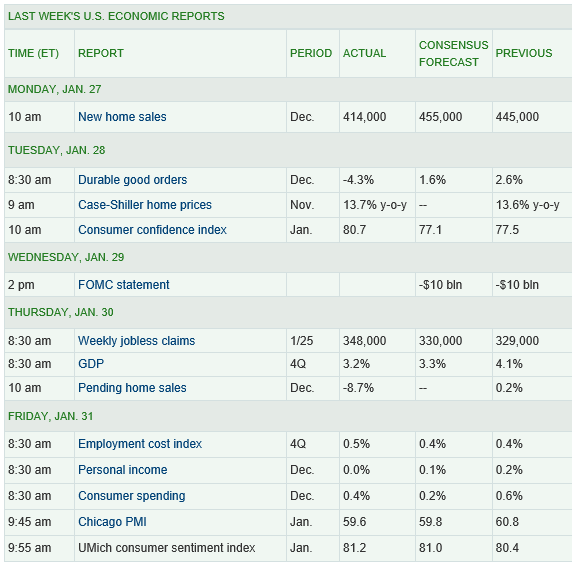

The Market Watch site publishes weekly median forecasts based on the 15 economists who have scored the highest in our contest over the past 12 months, as well as the forecasts of the most recent winner of the Forecaster of the Month contest.

The economists in the Market Watch consensus forecast include many currently or recently in the top twenty Bloomberg list – Jim O’Sullivan of High Frequency Economics, Michael Feroli of J.P. Morgan, Paul Edelstein of IHS Global Insight, Brian Jones of Société Générale, Spencer Staples of EconAlpha, Ted Wieseman of Morgan Stanley, Jan Hatzius’s team at Goldman Sachs, Stephen Stanley of Pierpont Securities, Avery Shenfeld of CIBC, Maury Harris’s team at UBS, Brian Wesbury and Robert Stein of First Trust, Jeffrey Rosen of Briefing.com, Paul Ashworth of Capital Economics, Julia Coronado of BNP Paribas, and Eric Green’s team at TD Securities.

And I like the format of doing retrospectives on these consensus forecasts, in tables such as this:

So what’s the bottom line here? Well, to me, digging deeper into the backgrounds of these top ranked forecasters, finding access to their current thinking is all part of improving competence.

I can think of no better mantra than Malcolm Gladwell’s 10,000 Hour Rule –