There’s rampant speculation and zero consensus about the direction OPEC will take in their upcoming Vienna meeting, November 27.

Last Friday, for example. Bloomberg reported,

The 20 analysts surveyed this week by Bloomberg are perfectly divided, with half forecasting the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries will cut supply on Nov. 27 in Vienna to stem a plunge in prices while the other half expect no change. In the seven years since the surveys began, it’s the first time participants were evenly split. The only episode that created a similar debate was the OPEC meeting in late 2007, when crude was soaring to a record.

Many discussions pose the strategic choice as one between –

(a) cutting production to maintain prices, but at the cost of losing market share to the ascendant US producers, and

(b) sustaining current production levels, thus impacting higher-cost US producers (if the low prices last long enough), but risking even lower oil prices – through speculation and producers breaking ranks and trying to grab what they can.

Lybia, Ecuador, and Venezuela are pushing for cuts in production. Saudi Arabia is not tipping its hand, but is seen by many as on the fence about reducing production.

I’m kind of a contrarian here. I think the sound and fury about this Vienna meeting on Thanksgiving may signify very little in terms of oil prices – unless global (and especially Chinese) economic growth picks up. As the dominant OPEC producer, Saudi Arabia may have market power, but, otherwise, there is little evidence OPEC functions as a cartel. It’s hard to see, also, that the Saudi’s would unilaterally reduce their output only to see higher oil prices support US frackers continuing to increase their production levels at current rates.

OPEC Members, Production, and Oil Prices

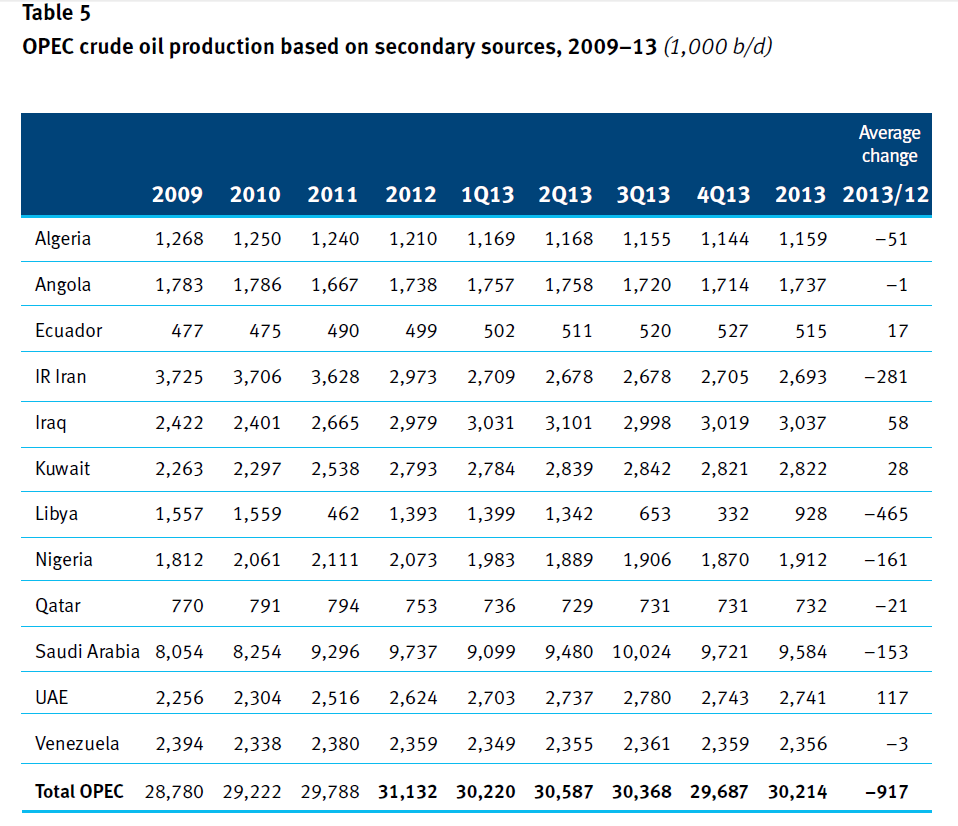

The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) has twelve members, whose production over recent years is documented in the following table.

According to the OPEC Annual Report, global oil supply in 2013 ran about 90.2 mb/d, while, as the above table indicates, OPEC production was 30.2 mb/d. So OPEC provided 33.4 percent of global oil supplies in 2013 with Saudi Arabia being the largest producer – overwhelmingly.

Oil prices, of course, have spiraled down toward $75 a barrel since last summer.

Is OPEC an Effective Cartel?

There is a growing literature questioning whether OPEC is an effective cartel.

This includes the recent OPEC: Market failure or power failure? which argues OPEC is not a working cartel and that Saudi Arabia’s ideal long term policy involves moderate prices guaranteed to assure continuing markets for their vast reserves.

Other recent studies include Does OPEC still exist as a cartel? An empirical investigation which deploys time series tests for cointegration and Granger causality, finding that OPEC is generally a price taker, although cartel-like features may adhere to a subgroup of its members.

The research I especially like, however, is by Jeff Colgan, a political scientist – The Emperor Has No Clothes: The Limits of OPEC in the Global Oil Market.

Colgan poses four tests of whether OPEC functions as a cartel -.

new members of the cartel have a decreasing or decelerating production rate (test #1); members should generally produce quantities at or below their assigned quota (test #2); changes in quotas should lead to changes in production, creating a correlation (test #3); and members of the cartel should generally produce lower quantities (i.e., deplete their oil at a lower rate) on average than non-members of the cartel (test #4)

Each of these tests fail, putting, as he writes, the burden of proof on those who would claim that OPEC is a cartel.

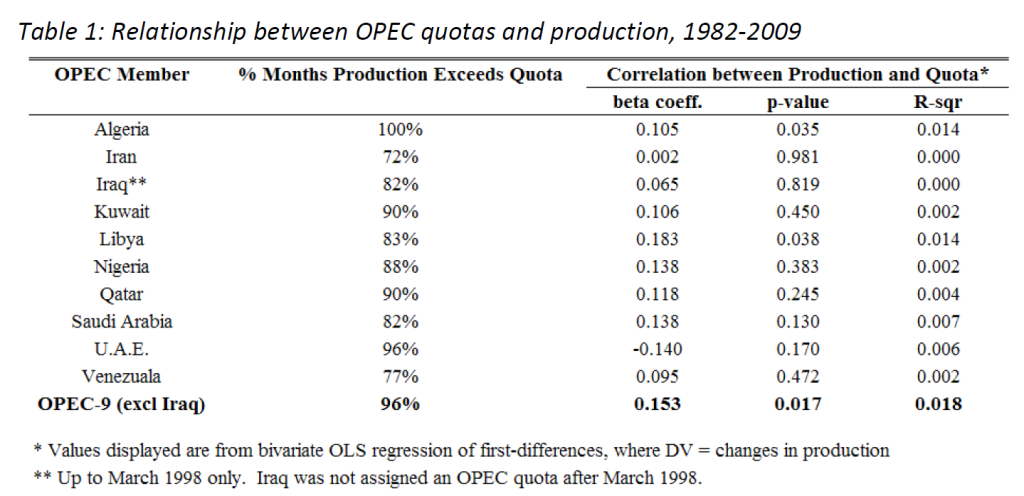

Here’s Colgan’s statistical analysis of cheating on the quotas.

On average, he calculates that the nine principal members of OPEC produced 10 percent more oil than their quotas allowed – which is equivalent to 1.8 million barrels per day, on average, which is more than the total daily output of Libya in 2009.

Finally, there is the extremely wonkish evidence from academic studies of oil and gas markets more generally.

There are, for example, several long term studies of cointegration of oil and gas markets. These studies rely on tests for unit roots which, as I have observed, have low statistical power. Nevertheless, the popularity of this hypothesis seems to be consistent with very little specific influence of OPEC on oil production and prices in recent decades. The 1970’s may well be an exception, it should be noted.

We will see in coming weeks. Or maybe not, since it still will be necessary to sort out influences such as quickening of the pace of economic growth in China with recent moves by the Chinese central bank to reduce interest rates and keep the bubble going.

If I were betting on this, however, I would opt for a continuation of oil prices below $100 a barrel, and probably below $90 a barrel for some time to come. Possibly even staying around $70 a barrel.