Like almost everyone who enjoys beer, wine, and mixed drinks, I have been interested in the research showing links between moderate alcohol consumption and cardiovascular health. In discussions with others, I’ve often heard, “now that’s the kind of scientific research we need more of” and so forth.

But obviously, booze is a two-edge sword.

So this research by Dr. James O’Keefe, a cardiologist from Mid America Heart Institute, with his co-authors Dr. Salman K. Bhatti, Dr. Ata Bajwa, James J. DiNicolantonio, Doctor of Pharmacy, and Dr. Carl J. Lavie caught my eye, because its comprehensive review of the literature on both benefits and risks.

It was published in the Mayo Clinic Proceedings, and here Dr. O’Keefe summarizing the findings.

The Abstract for this research paper, Alcohol and Cardiovascular Health: The Dose Makes the Poison…or the Remedy, lays it out pretty clearly.

Habitual light to moderate alcohol intake (up to 1 drink per day for women and 1 or 2 drinks per day for men) is associated with decreased risks for total mortality, coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, and stroke. However, higher levels of alcohol consumption are associated with increased cardiovascular risk. Indeed, behind only smoking and obesity, excessive alcohol consumption is the third leading cause of premature death in the United States. Heavy alcohol use (1) is one of the most common causes of reversible hypertension, (2) accounts for about one-third of all cases of nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy, (3) is a frequent cause of atrial fibrillation, and (4) markedly increases risks of stroke—both ischemic and hemorrhagic. The risk-to-benefit ratio of drinking appears higher in younger individuals, who also have higher rates of excessive or binge drinking and more frequently have adverse consequences of acute intoxication (for example, accidents, violence, and social strife). In fact, among males aged 15 to 59 years, alcohol abuse is the leading risk factor for premature death. Of the various drinking patterns, daily low- to moderate-dose alcohol intake, ideally red wine before or during the evening meal, is associated with the strongest reduction in adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Health care professionals should not recommend alcohol to nondrinkers because of the paucity of randomized outcome data and the potential for problem drinking even among individuals at apparently low risk. The findings in this review were based on a literature search of PubMed for the 15-year period 1997 through 2012 using the search terms alcohol, ethanol, cardiovascular disease, coronary artery disease, heart failure, hypertension, stroke, and mortality. Studies were considered if they were deemed to be of high quality, objective, and methodologically sound.

Did someone say there is no such thing as a free lunch? Note, “among males aged 15 to 59 years, alcohol abuse is the leading risk factor for premature death.”

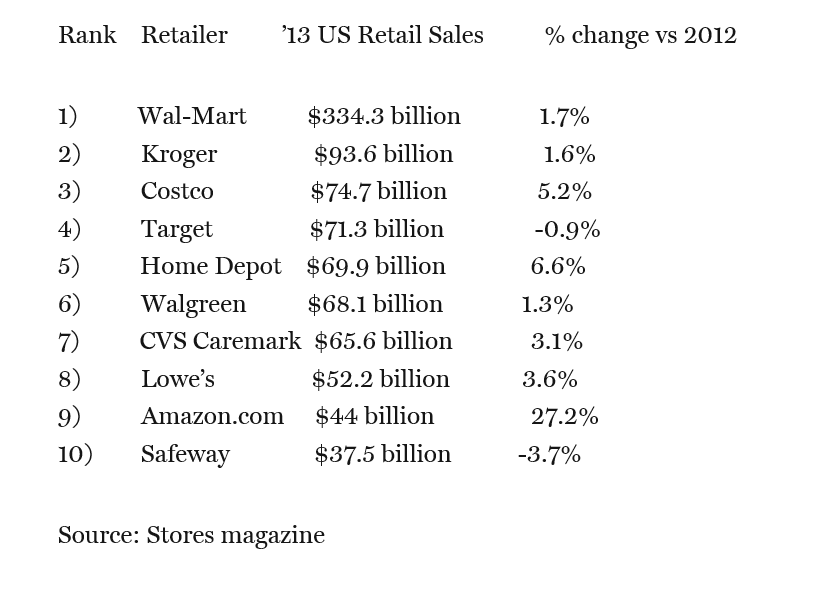

There is some moral here, possibly related to the size of the US booze industry, an estimated $331 billions in 2011 about equally distributed between beer and for the other part wine and hard liquor.

Also I wonder with the growing legal acceptance of marijuana at the state level in the US, whether negative health impacts would be mitigated by substitution of weed for drinking. Of course, combination of both is a possibility, leading to drug-crazed drunks?

Maybe the more important issue is to bring people’s unquestionable desire for mind-altering substances into focus, to understand this urge, and be able to develop cultural contexts in which moderate usage can take place.