Is climate change real? Is it predictable? How much warming can we expect by 2020 and then by 2030 in a business as usual scenario? How bad can it get? What about mitigation? Is there any credibility to the loud protestations of the climate change deniers? What about the so-called hockey stick and the exchange of sinister emails?

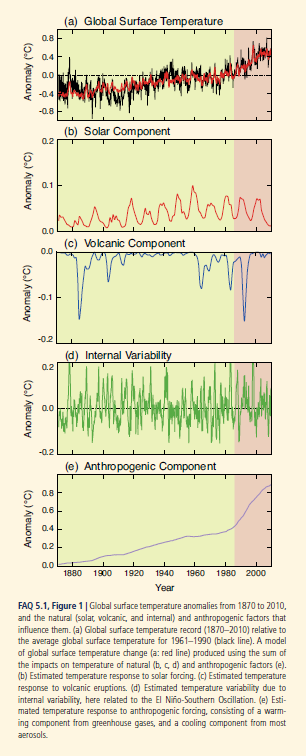

The Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) addresses some of these questions. Its section The Physical Science Basis, which collates contributions of 250 scientists, contains this interesting graphic (click to enlarge) showing the upward trend in global temperature and the importance of the anthropogenic component, along with contributions from fluctuations in solar intensity and volcanic activity.

The Hockey Stick

Paleoclimate studies, also documented in this report, are the basis for the famous (notorious) hockey stick chart of long term global temperatures.

I was surprised to read, in catching up on this controversy, that the climate scientist Michael Mann who originated this chart has been totally vindicated (See The Hockey Stick: The Most Controversial Chart in Science, Explained).

Currently, scientific evidence suggests,

The Drumbeat

In preparation for a September 23 summit, the UN has commissioned videos of weather forecasters supposedly announcing dire droughts, floods, and other weather catastrophes in 2050.

The IPCC also has videos. I include two – one on the physical science basis and the second on mitigation.

IPCC video 2013 –The Physical Science Basis

Climate summit 2014 – Mitigation

I personally am persuaded by the basic physics involved. As global GDP rises, so will energy consumption (although the details of this need to be examined carefully – conservation and change of technology can make big differences). In any case, more carbon dioxide and other similar gases will increase the greenhouse effect, raising global temperatures. It’s a good idea to call this climate change, rather than global warming, however, since volatility of weather patterns is a main result. There will be more climatic extremes, more droughts, but also more precipitation and flooding. Additionally, there could be changes in regional weather and climate patterns which could wreak havoc with the current distribution of population over geographic space. More rapid desertification is likely, and, of course, melting of glacial and polar ice will result in increases in sea level. And, as IPCC reports document, a lot of this is already happening.

There are, however, several problems that offer intellectual grounds for stalling the type of economic sacrifice that probably will be necessary to slow or reduce emissions.

First, there is the complexity of the evidence and argument, an issue flagged by Nate Silver recently. Secondly, there is the problem that, despite increases in greenhouse gas emissions after the turn of the century, there has been some leveling of global temperature increase, according to some metrics. Finally, there is the related problem of whether current climate models predict the recent past, whether they “retrodict.”

I’d like to address these issues or problems in a future post, along with my take on these projections or forecasts for 2020 and 2030.