I’m interested in everything under the sun relating to forecasting – including sunspots (another future post). But the focus on medicine and health is special for me, since my closest companion, until her untimely death a few years ago, was a physician. So I pay particular attention to details on forecasting in medicine and health, with my conversations from the past somewhat in mind.

There is a major area which needs attention for any kind of completion of a first pass on this subject – forecasting epidemics.

Several major diseases ebb and flow according to a pattern many describe as an epidemic or outbreak – influenza being the most familiar to people in North America.

I’ve already posted on the controversy over Google flu trends, which still seems to be underperforming, judging from the 2013-2014 flu season numbers.

However, combining Google flu trends with other forecasting models, and, possibly, additional data, is reported to produce improved forecasts. In other words, there is information there.

In tropical areas, malaria and dengue fever, both carried by mosquitos, have seasonal patterns and time profiles that health authorities need to anticipate to stock supplies to keep fatalities lower and take other preparatory steps.

Early Warning Systems

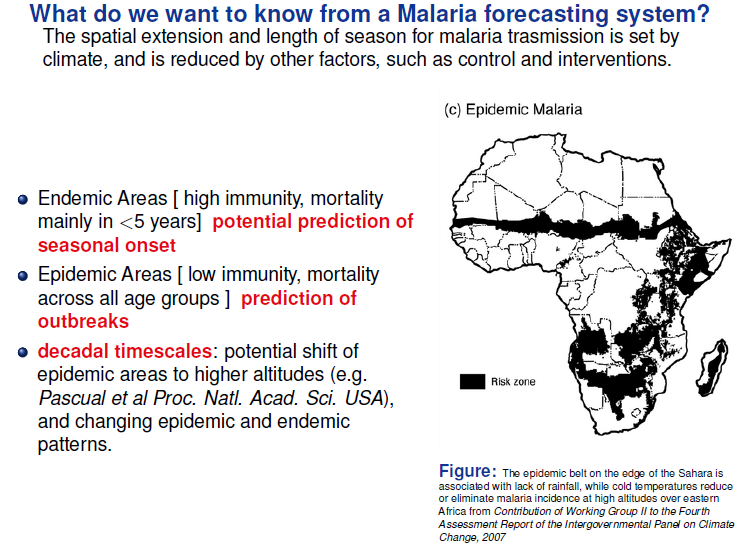

The following slide from A Prototype Malaria Forecasting System illustrates the promise of early warning systems, keying off of weather and climatic predictions.

There is a marked seasonal pattern, in other words, to malaria outbreaks, and this pattern is linked with developments in weather.

Researchers from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, for example, recently demonstrated that temperatures in a large area of the tropical South Atlantic are directly correlated with the size of malaria outbreaks in India each year – lower sea surface temperatures led to changes in how the atmosphere over the ocean behaved and, over time, led to increased rainfall in India.

Another mosquito-borne disease claiming many thousands of lives each year is dengue fever.

And there is interesting, sophisticated research detailing the development of an early warning system for climate-sensitive disease risk from dengue epidemics in Brazil.

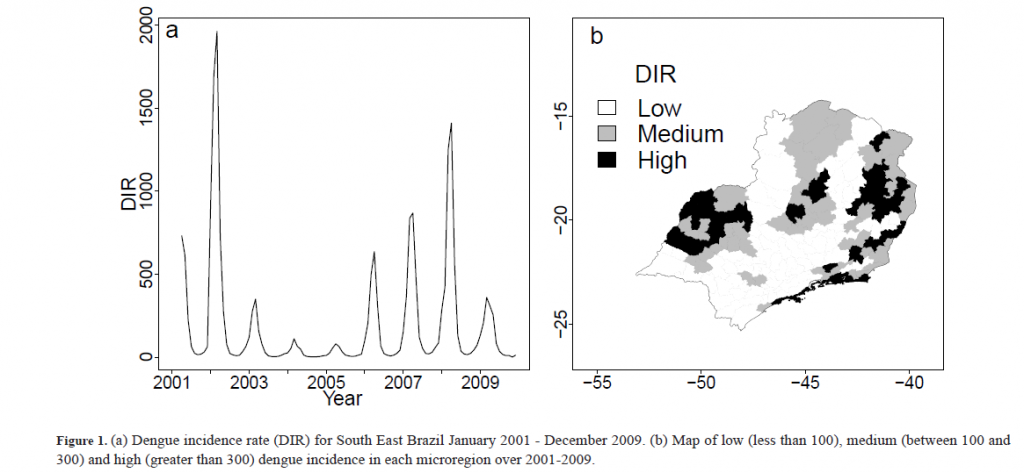

The following exhibits show the strong seasonality of dengue outbreaks, and a revealing mapping application, showing geographic location of high incidence areas.

This research used out-of-sample data to test the performance of the forecasting model.

The model was compared to a simple conceptual model of current practice, based on dengue cases three months previously. It was found that the developed model including climate, past dengue risk and observed and unobserved confounding factors, enhanced dengue predictions compared to model based on past dengue risk alone.

MERS

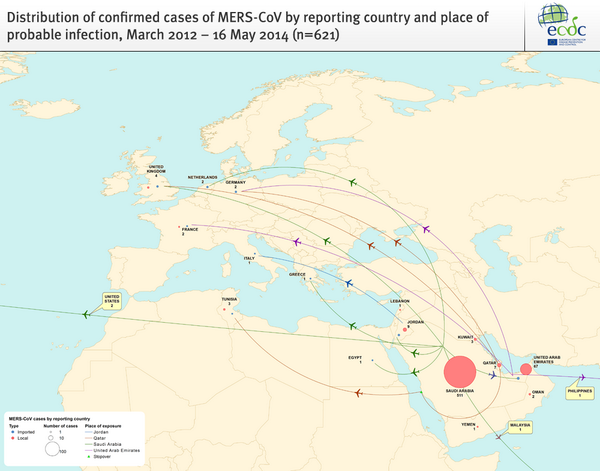

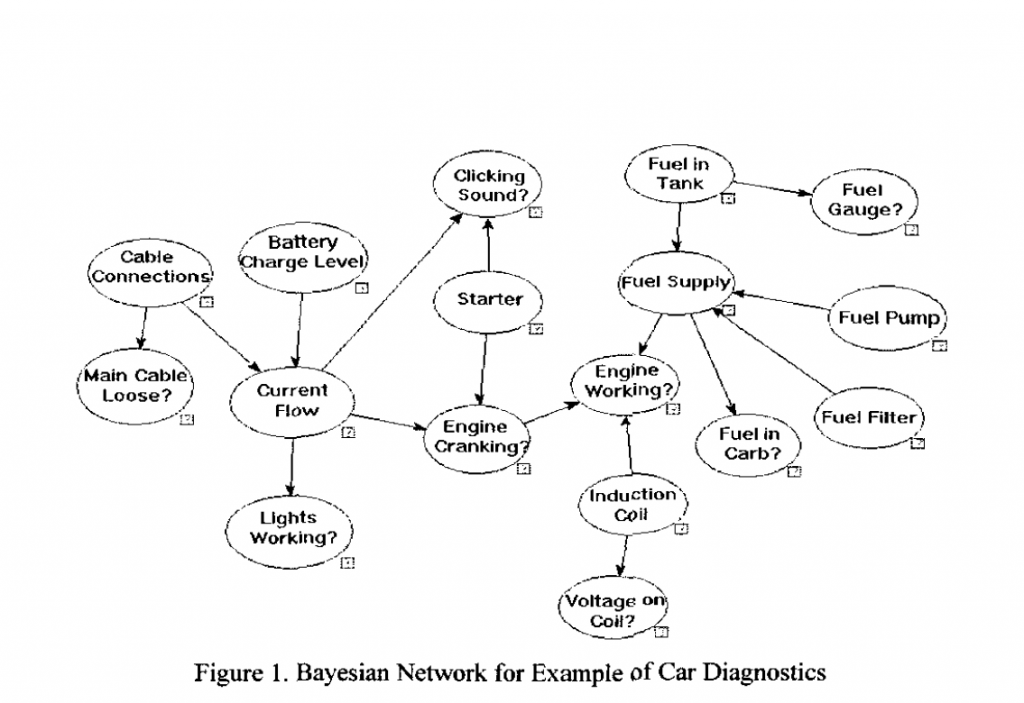

The latest global threat, of course, is MERS – or Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, which is a coronavirus, It’s transmission from source areas in Saudi Arabia is pointedly suggested by the following graphic.

The World Health Organization is, as yet, refusing to declare MERS a global health emergency. Instead, spokesmen for the organization say,

..that much of the recent surge in cases was from large outbreaks of MERS in hospitals in Saudi Arabia, where some emergency rooms are crowded and infection control and prevention are “sub-optimal.” The WHO group called for all hospitals to immediately strengthen infection prevention and control measures. Basic steps, such as washing hands and proper use of gloves and masks, would have an immediate impact on reducing the number of cases..

Millions of people, of course, will travel to Saudi Arabia for Ramadan in July and the hajj in October. Thirty percent of the cases so far diagnosed have resulted in fatalties.