In the previous post, I drew from papers by Neeley, who is Vice President of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, David Rapach at St. Louis University and Goufu Zhou at Washington University in St. Louis.

These authors contribute two papers on the predictability of equity returns.

The earlier one – Forecasting the Equity Risk Premium: The Role of Technical Indicators – is coming out in Management Science. Of course, the survey article – Forecasting the Equity Risk Premium: The Role of Technical Indicators – is a chapter in the recent volume 2 of the Handbook of Forecasting.

I go through this rather laborious set of citations because it turns out that there is an underlying paper which provides the data for the research of these authors, but which comes to precisely the opposite conclusion –

The goal of our own article is to comprehensively re-examine the empirical evidence as of early 2006, evaluating each variable using the same methods (mostly, but not only, in linear models), time-periods, and estimation frequencies. The evidence suggests that most models are unstable or even spurious. Most models are no longer significant even insample (IS), and the few models that still are usually fail simple regression diagnostics.Most models have performed poorly for over 30 years IS. For many models, any earlier apparent statistical significance was often based exclusively on years up to and especially on the years of the Oil Shock of 1973–1975. Most models have poor out-of-sample (OOS) performance, but not in a way that merely suggests lower power than IS tests. They predict poorly late in the sample, not early in the sample. (For many variables, we have difficulty finding robust statistical significance even when they are examined only during their most favorable contiguous OOS sub-period.) Finally, the OOS performance is not only a useful model diagnostic for the IS regressions but also interesting in itself for an investor who had sought to use these models for market-timing. Our evidence suggests that the models would not have helped such an investor. Therefore, although it is possible to search for, to occasionally stumble upon, and then to defend some seemingly statistically significant models, we interpret our results to suggest that a healthy skepticism is appropriate when it comes to predicting the equity premium, at least as of early 2006. The models do not seem robust.

This is from Ivo Welch and Amit Goyal’s 2008 article A Comprehensive Look at The Empirical Performance of Equity Premium Prediction in the Review of Financial Studies which apparently won an award from that journal as the best paper for the year.

And, very importantly, the data for this whole discussion is available, with updates, from Amit Goyal’s site now at the University of Lausanne.

Where This Is Going

Currently, for me, this seems like a genuine controversy in the forecasting literature. And, as an aside, in writing this blog I’ve entertained the notion that maybe I am on the edge of a new form of or focus in journalism – namely stories about forecasting controversies. It’s kind of wonkish, but the issues can be really, really important.

I also have a “hands-on” philosophy, when it comes to this sort of information. I much rather explore actual data and run my own estimates, than pick through theoretical arguments.

So anyway, given that Goyal generously provides updated versions of the data series he and Welch originally used in their Review of Financial Studies article, there should be some opportunity to check this whole matter. After all, the estimation issues are not very difficult, insofar as the first level of argument relates primarily to the efficacy of simple bivariate regressions.

By the way, it’s really cool data.

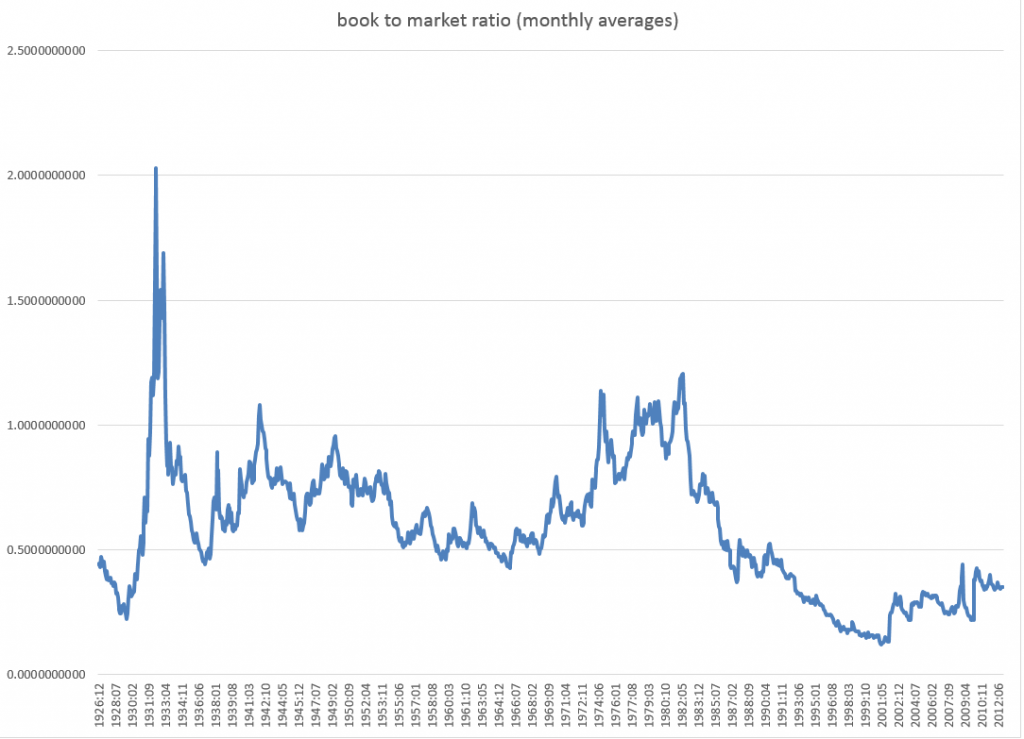

Here is the book-to-market ratio, dating back to 1926.

But beyond these simple regressions that form a large part of the argument, there is another claim made by Neeley, Rapach, and Zhou which I take very seriously. And this is that – while a “kitchen sink” model with all, say, fourteen so-called macroeconomic variables does not outperform the benchmark, a principal components regression does.

This sounds really plausible.

Anyway, if readers have flagged updates to this controversy about the predictability of stock market returns, let me know. In addition to grubbing around with the data, I am searching for additional analysis of this point.