The US Federal Reserve Bank declared an end to its quantitative easing (QE) program at the end of October.

QE involves direct Fed intervention into buying longer term bonds with an eye to exercising leverage on long term interest rates and, thus, encouraging investment. Readers wanting more detail on how QE is implemented – check Ed Dolan’s slide show Quantitative Easing and the Fed 2008-2014: A Tutorial

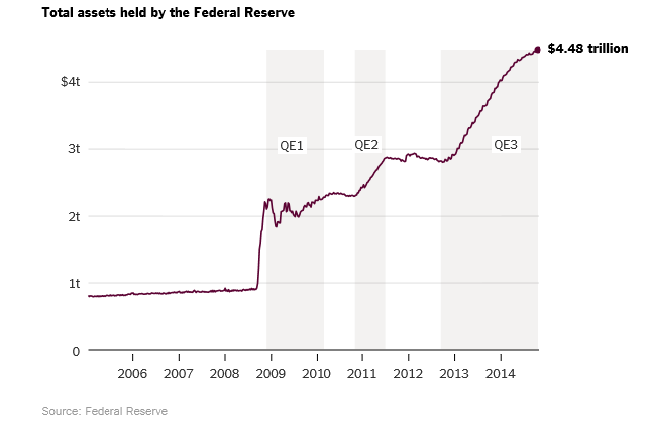

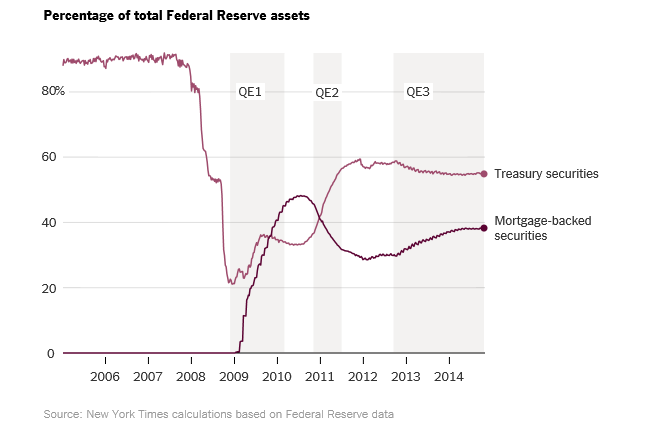

The New York Times article on the Fed actions – Quantitative Easing Is Ending. Here’s What It Did, in Charts – had at least two charts that are must-see’s.

First, the ballooning of the Federal Reserve Balance sheet from less than $1 trillion to $4.5 trillion today –

Secondly, according to Times estimates, about 40 percent of Fed assets are comprised of mortgage-backed securities now – making the Fed a potential major player in the US housing markets.

Several recent articles offer interpretation – what does the end of this five-year long program mean for the US economy and for investors. What were the impacts of QE?

I thought Jeff Miller’s “Old Prof” compendium was especially good – Weighing the Week Ahead: What the End of QE Means for the Individual Investor. If you click this link and find a post more recent than November 1, scroll down for the QE discussion. Basically, Miller thinks the impact on investors will be minimal.

This is also true in the Business Week article The Hawaiian Tropic Effect: Why the Fed’s Quantitative Easing Isn’t Over

But quantitative easing is the gift that keeps on giving. Even after the purchases end, its effects will persist. How could that be? The Fed will still own all those bonds it bought, and according to the agency itself, it’s the level of its holdings that affects the bond market, not the rate of addition to those holdings. Having reduced the supply of bonds available on the market, the Fed has raised their price. Yields (i.e. market interest rates) go down when prices go up. So the effect of quantitative easing is to lower interest rates for things Americans actually care about, such as 30-year fixed-rate mortgages.

Some other articles which attempt to tease out exactly what impacts QE did have on the economy –

Evaluation of quantitative easing QE had “some effects” but it’s one of several influences on the bond market and long term interest rates.

Quantitative easing: giving cash to the public would have been more effective

QE has also had unforeseen side-effects. The policy involved allowing banks and other financial institutions to exchange bonds for cash, and the hope was that this would lead to improved flows of credit to firms looking to expand. In reality, it encouraged financial speculation in property, shares and commodities. The bankers and the hedge fund owners did well out of QE, but the side-effect of footloose money searching the globe for high yields was higher food and fuel prices. High inflation and minimal wage growth led to falling real incomes and a slower recovery.

What Quantitative Easing Did Not Do: Three Revealing Charts – good discussion organized around the following three points –

- QE did not work according to the textbook model

- QE did not cause inflation

- QE was not powerful enough to overcome fiscal restraint

Expansion of QE

But quantitative easing as a central bank policy is by no means a dead letter.

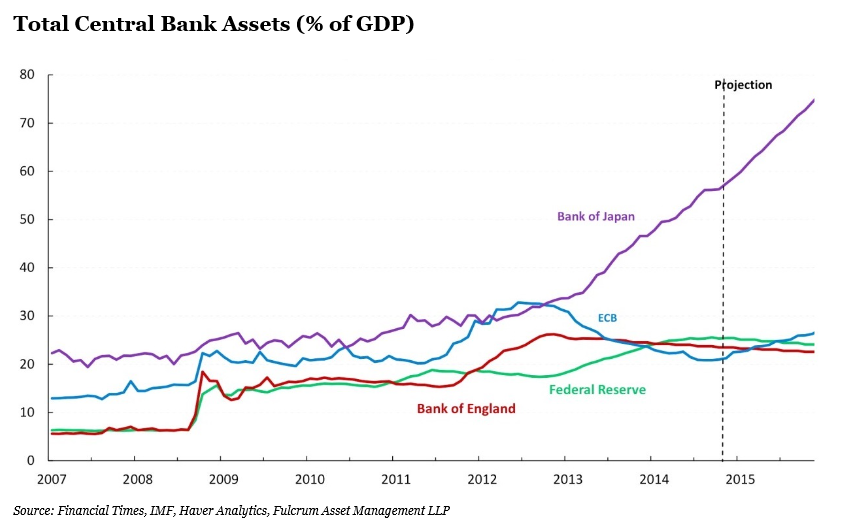

In fact, at the very moment the US Federal Reserve announced the end of its five-year long program of bond-buying, the Bank of Japan (BOPJ) announced a significant expansion of its QE, as noted in this article from Forbes.

Last week, as the Federal Reserve officially announced the end of its long-term asset purchase program (commonly known as QE3), the Bank of Japan significantly ratcheted up its own quantitative easing program, in a surprising 5-4 split decision. Starting next year, the Bank of Japan will increase its balance sheet by 15 percent of GDP per annum and will extend the average duration of its bond purchases from 7 years to 10 years. The big move by Japan’s central bank comes amid the country’s GDP declining by 7.1% in the second quarter of 2014 (on an annualized basis) from the previous quarter following the increase of the VAT sales tax from 5% to 8% in Japan earlier this year and worries that Japan could fall into another deflationary spiral..

The scale of the Japanese effort is truly staggering, as this chart from the Forbes article illustrates.

The Economist article on this development Every man for himself tries to work out the implications of the Japanese action on the value of the yen, Japanese inflation/deflation, the Japanese international trade position, impact on competitors (China), and impacts on the US dollar.

What about Europe? Well, Bloomberg offers this primer – Europe’s QE Quandary. Short take – there are 18 nations which have to agree and move together, Germany’s support being decisive. But deflation appears to be spreading in Europe, so many expect something to be done along QE lines.

If you are forecasting for businesses, government agencies, or investors, these developments by central banks around the world are critically important. Their effects may be subtle and largely in unintended consequences, but the scale of operations means you simply have to keep track.