Crude oil futures continue their descent, as the chart below from January 2, 2015 shows.

What is going to happen here?

Discussions organize around several issues, pretty well nailed recently by IMF bloggers (including Chief Economist Oliver Blanchard) in Seven Questions About The Recent Oil Price Slump.

- What are the respective roles of demand and supply factors?

- How persistent is this supply shift likely to be?

- What are the effects likely to be on the global economy?

- What are likely to be the effects on oil importers?

- What are likely to be the effects on oil exporters?

- What are the financial implications?

- What should be the policy response of oil importers and exporters?

The first point to note is the drop in oil prices involves both supply and demand – and is not just the result of increased pumping by Saudi Arabia.

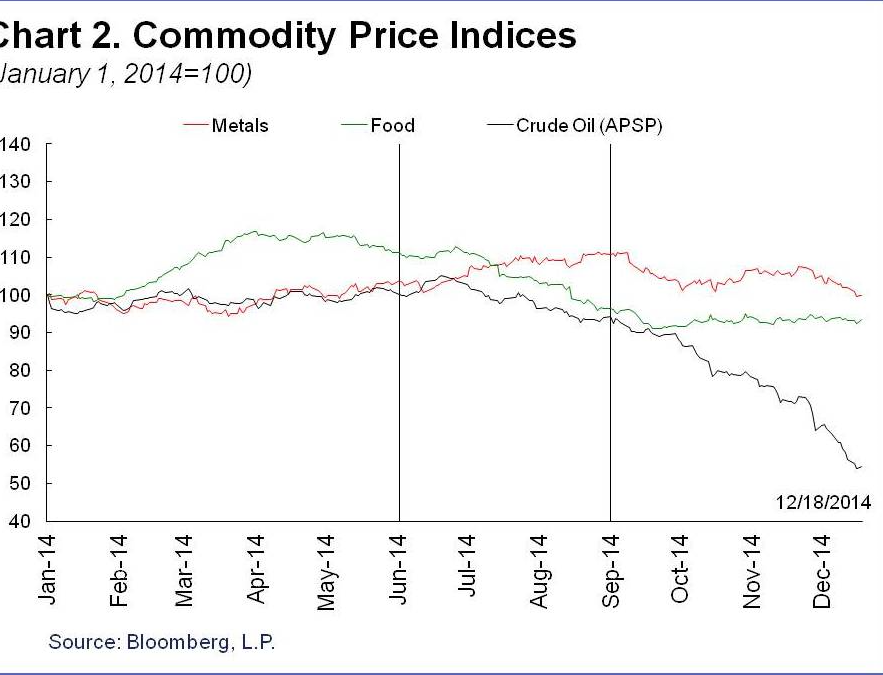

The IMF discussion includes this interesting comparison between oil and other commodity price indices.

So over 2014, there have been drops in other commodity prices – probably due to weakened global demand – but not nearly much as oil.

Overall, the IMF counts lower oil prices as a net positive to the global economy, resulting in a gain for world GDP between 0.3 and 0.7 percent in 2015, compared to a scenario without the drop in oil prices.

There are big losers, of course. These include oil exporters with higher production costs, such as Russia, Iran, and Venezuela.

To take some examples, energy accounts for 25 percent of Russia’s GDP, 70 percent of its exports, and 50 percent of federal revenues. In the Middle East, the share of oil in federal government revenue is 22.5 percent of GDP and 63.6 percent of exports for the Gulf Cooperation Council countries. In Africa, oil exports accounts for 40-50 percent of GDP for Gabon, Angola and the Republic of Congo, and 80 percent of GDP for Equatorial Guinea. Oil also accounts for 75 percent of government revenues in Angola, Republic of Congo and Equatorial Guinea. In Latin America, oil contributes respectively about 30 percent and 46.6 percent to public sector revenues, and about 55 percent and 94 percent of exports for Ecuador and Venezuela.[8] This shows the dimension of the challenge facing these countries.

How long the Saudi’s can hold the line, maintaining higher production? Is it true, for example, that Saudi Arabia has a $750bn war chest of foreign currency reserves that will be burned through quickly by propping up the shortfall in export revenues? There are speculations that the health of King Abdullah, a strong supporter of the current Saudi Oil Minister, could come into play in coming months.

Interestingly, low oil prices maintained long enough could be self-correcting. This is probably the bet the Saudi’s are making – that their policy can eventually trigger faster growth and enable them to maintain or increase their market share.

As I’ve said before, I think it’s a game changer. The trick is to figure out the linkages and connections, backwards and forwards along the supply chains.

Image of King Abdullah from Telegraph.