In many business applications, forecasting is not a hugely complex business. For a sales forecasting, the main challenge can be obtaining the data, which may require sifting through databases compiled before and after mergers or other reorganizations. Often, available historical data goes back only three or four years, before which time product cycles make comparisons iffy. Then, typically, you plug the sales data into an automatic forecasting program, one that can assess potential seasonality, and probably employing some type of exponential smoothing, and, bang, you produce forecasts for one to several quarters going forward.

The situation becomes more complex when you take into account various drivers and triggers for sales. The customer revenues and income are major drivers, which lead into assessments of business conditions generally. Maybe you want to evaluate the chances of a major change in government policy or the legal framework – both which are classifiable under “triggers.” What if the Federal Reserve starts raising the interest rates, for example.

For many applications, a driver-trigger matrix can be useful. This is a qualitative tool for presentations to management. Essentially, it helps keep track of assumptions about the scenarios which you expect to unfold from which you can glean directions of change for the drivers – GDP, interest rates, market conditions. You list the major influences on sales in the first column. In the second column you indicate the direction of this influences (+/-) and in the third column you put in the expected direction of change, plus, minus, or no change.

The next step up in terms of complexity is to collect historical data on the drivers and triggers – “explanatory variables” driving sales in the company. This opens the way for a full-blown multivariate model of sales performance. The hitch is to make this operational, you have to forecast the explanatory variables. Usually, this is done by relying, again, on forecasts by other organizations, such as market research vendors, consensus forecasts such as available from the Survey of Professional Forecasters and so forth. Sometimes it is possible to identify “leading indicators” which can be built into multivariate models. This is really the best of all possible worlds, since you can plug in known values of drivers and get a prediction for the target variable.

The value of forecasting to a business is linked with benefits of improvements in accuracy, as well as providing a platform to explore “what-if’s,” supporting learning about the business, customers, and so forth.

With close analysis, it is often possible to improve the accuracy of sales forecasts by a few percentage points. This may not sound like much, but in a business with $100 million or more in sales, competent forecasting can pay for itself several times over in terms of better inventory management and purchasing, customer satisfaction, and deployment of resources.

Time Horizon

When you get a forecasting assignment, you soon learn about several different time horizons. To some extent, each forecasting time horizon is best approached with certain methods and has different uses.

Conventionally, there are short, medium, and long term forecasting horizons.

In general business applications, the medium term perspective of a few quarters to a year or two is probably the first place forecasting is deployed. The issue is usually the budget, and allocating resources in the organization generally. Exponential smoothing, possibly combined with information about anticipated changes in key drivers, usually works well in this context. Forecast accuracy is a real consideration, since retrospectives on the budget are a common practice. How did we do last year? What mistakes were made? How can we do better?

The longer term forecast horizons of several years or more usually support planning, investment evaluation, business strategy. The M-competitions suggest the issue has to be being able to pose and answer various “what-if’s,” rather than achieving a high degree of accuracy. Of course, I refer here to the finding that forecast accuracy almost always deteriorates in direct proportion to the length of the forecast horizon.

Short term forecasting of days, weeks, a few months is an interesting application. Usually, there is an operational focus. Very short term forecasting in terms of minutes, hours, days is almost strictly a matter of adjusting a system, such as generating electric power from a variety of sources, i.e. combining hydro and gas fired turbines, etc.

As far as techniques, short term forecasting can get sophisticated and mathematically complex. If you are developing a model for minute-by-minute optimization of a system, you may have several months or even years of data at your disposal. There are, thus, more than a half a million minutes in a year.

Forecasting and Executive Decisions

The longer the forecasting horizon, the more the forecasting function becomes simply to “inform judgment.”

A smart policy for an executive is to look at several forecasts, consider several sources of information, before determining a policy or course of action. Management brings judgment to bear on the numbers. It’s probably not smart to just take the numbers on blind faith. Usually, executives, if they pay attention to a presentation, will insist on a coherent story behind the model and the findings, and also checking the accuracy of some points. Numbers need to compute. Round-off-errors need to be buried for purposes of the presentation. Everything should add up exactly.

As forecasts are developed for shorter time horizons and more for direct operation control of processes, acceptance and use of the forecast can become more automatic. This also can be risky, since developers constantly have to ask whether the output of the model is reasonable, whether the model is still working with the new data, and so forth.

Shiny New Techniques

The gap between what is theoretically possible in data analysis and what is actually done is probably widening. Companies enthusiastically take up the “Big Data” mantra – hiring “Chief Data Scientists.” I noticed with amusement an article in a trade magazine quoting an executive who wondered whether hiring a data scientist was something like hiring a unicorn.

There is a lot of data out there, more all the time. More and more data is becoming accessible with expansion of storage capabilities and of course storage in the cloud.

And really the range of new techniques is dazzling.

I’m thinking, for example, of bagging and boosting forecast models. Or of the techniques that can be deployed for the problem of “many predictors,” techniques including principal component analysis, ridge regression, the lasso, and partial least squares.

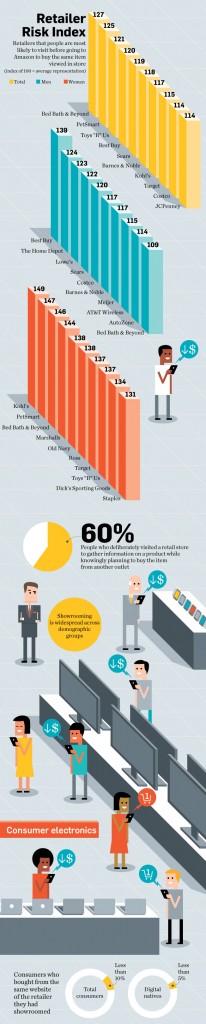

Probably one of the areas where these new techniques come into their own is in target marketing. Target marketing is kind of a reworking of forecasting. As in forecasting sales generally, you identify key influences (“drivers and triggers”) on the sale of a product, usually against survey data or past data on customers and their purchases. Typically, there is a higher degree of disaggregation, often to the customer level, than in standard forecasting.

When you are able to predict sales to a segment of customers, or to customers with certain characteristics, you then are ready for the sales campaign to this target group. Maybe a pricing decision is involved, or development of a product with a particular mix of features. Advertising, where attitudinal surveys supplement customer demographics and other data, is another key area.

Related Areas

Many of the same techniques, perhaps with minor modifications, are applicable to other areas for what has come to be called “predictive analytics.”

The medical/health field has a growing list of important applications. As this blog tries to show, quantitative techniques, such as logistic regression, have a lot to offer medical diagnostics. I think the extension of predictive analytics to medicine and health care ism at this point, merely a matter of access to the data. This is low-hanging fruit. Physicians diagnosing a guy with an enlarged prostate and certain PSA and other metrics should be able to consult a huge database for similarities with respect to age, health status, collateral medical issues and so forth. There is really no reason to suspect that normally bright, motivated people who progress through medical school and come out to practice should know the patterns in 100,000 medical records of similar cases throughout the nation, or have read all the scientific articles on that particular niche. While there are technical and interpretive issues, I think this corresponds well to what Nate Silver identifies as promising – areas where application of a little quantitative analysis and study can reap huge rewards.

And cancer research is coming to be closely allied with predictive analytics and data science. The paradigmatic application is the DNA assay, where a sample of a tumor is compared with healthy tissue from the same individual to get an idea of what cancer configuration is at play. Indeed, at that fine new day when big pharma will develop hundreds of genetically targeted therapies for people with a certain genetic makeup with a certain cancer – when that wonderful new day comes – cancer treatment may indeed go hand in hand with mathematical analysis of the patient’s makeup.