Today, I take a brief look at economic forecasts available from Morgan Stanley, Wells Fargo, and the French concern Credit Agricole. As readers will note, Morgan Stanley has a lively discussion of the implications of the US midterms, while Wells Fargo has a very comprehensive and easy-to-access series of economic projections, ranging from weekly, to monthly and annual. Credit Agricole (apologies for omitting the accent mark) is the first European bank profiled in these brief looks, and has quarterly updates of fairly comprehensive economic projections across a range of variables.

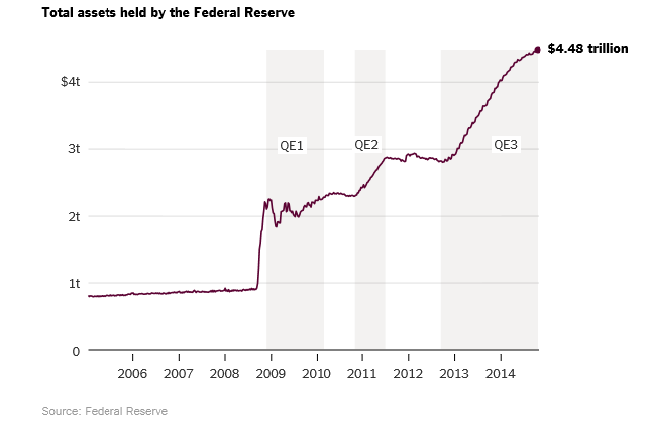

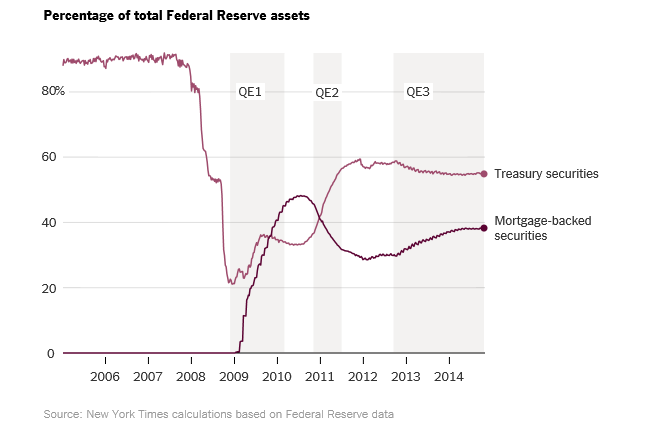

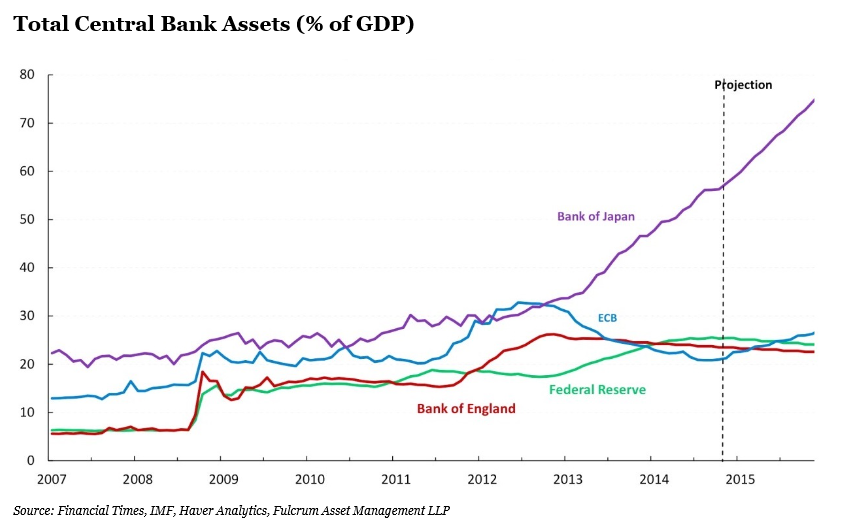

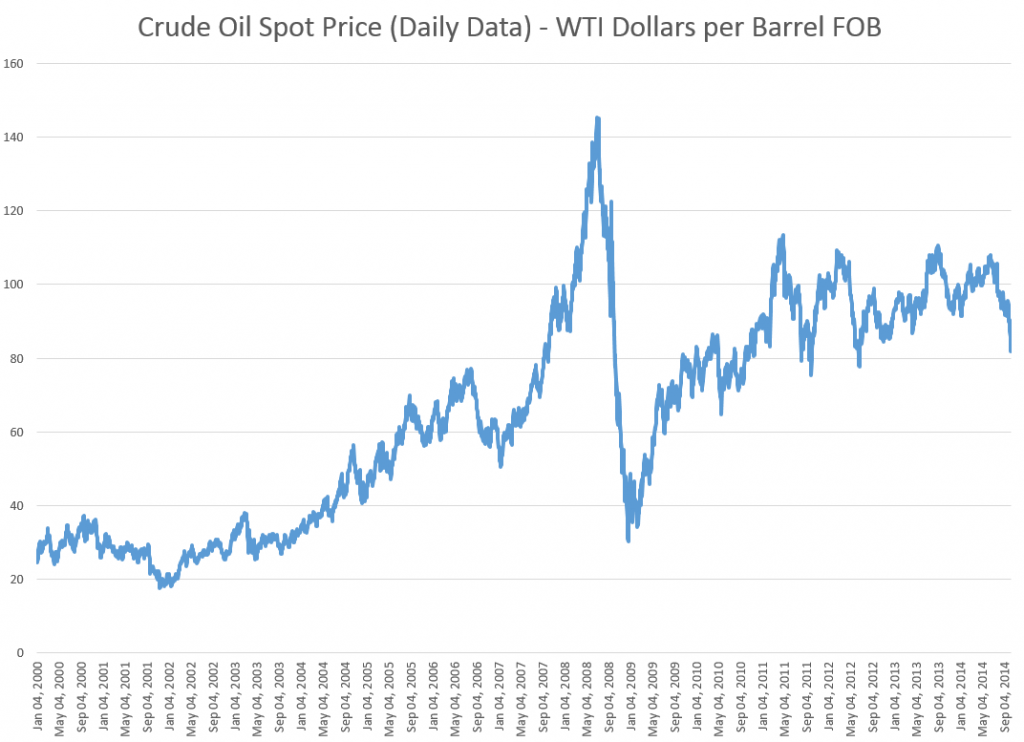

And I might mention that these publications, which date back into September in many cases, are interesting to review both because of their projections and because of what they miss – notably the drop in oil prices and aggressive new round of quantitative easing by the Bank of Japan.

The fact these developments are missed in these September and even later releases qualifies them as genuine surprises. Thus, their impacts are not discounted in past market developments, and, going forward, oil prices and Japan QE could exert significant, discrete effects on markets.

Morgan Stanley

According to the Federal Reserve’s National Information Center, Morgan Stanley is the nation’s 6th largest bank.

The Global Investment Committee (GOC) Weekly for November 10 is notable for some straight talk on the Implications of the US midterms, which Morgan Stanley see as slightly pro-growth, positive for equities, with constructive compromises, characteristic of lame duck presidencies. I quote fairly extensively, because the frankness of the insights and suggestions is refreshing.

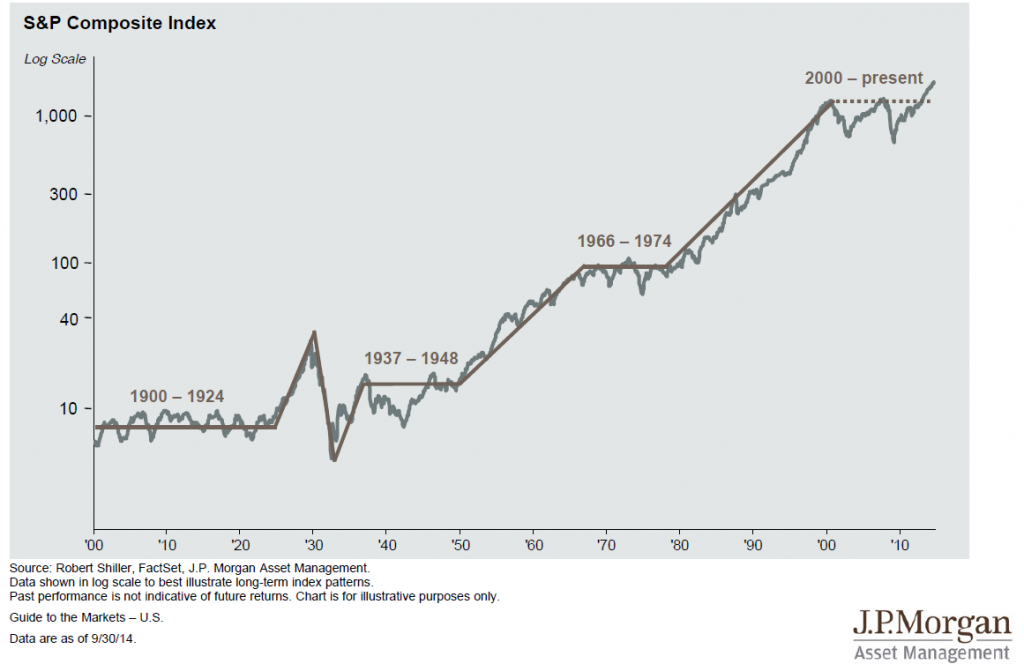

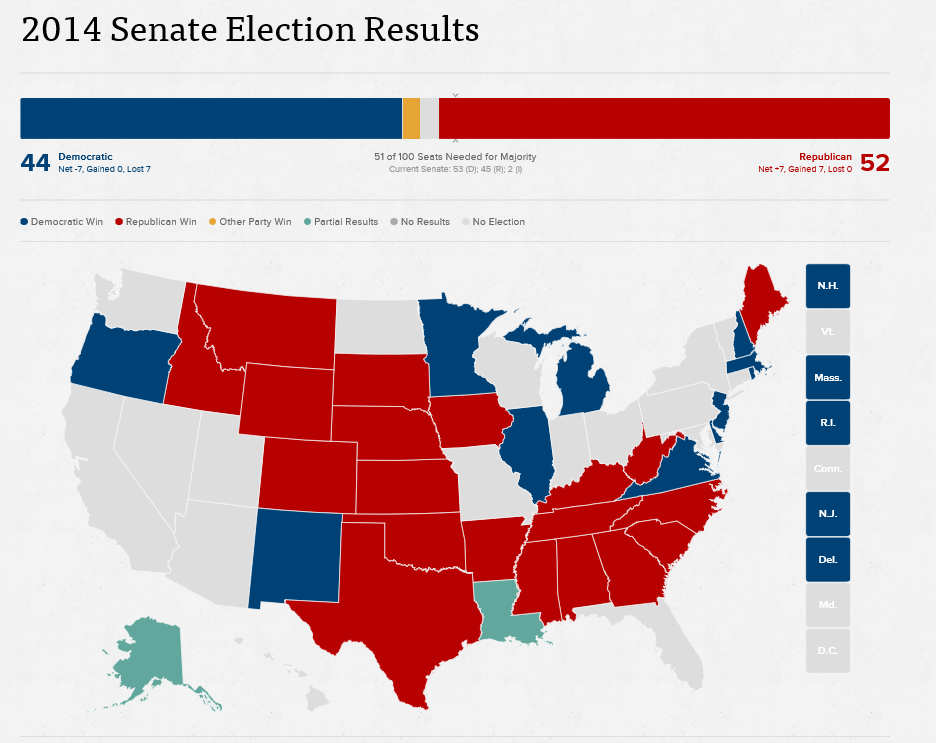

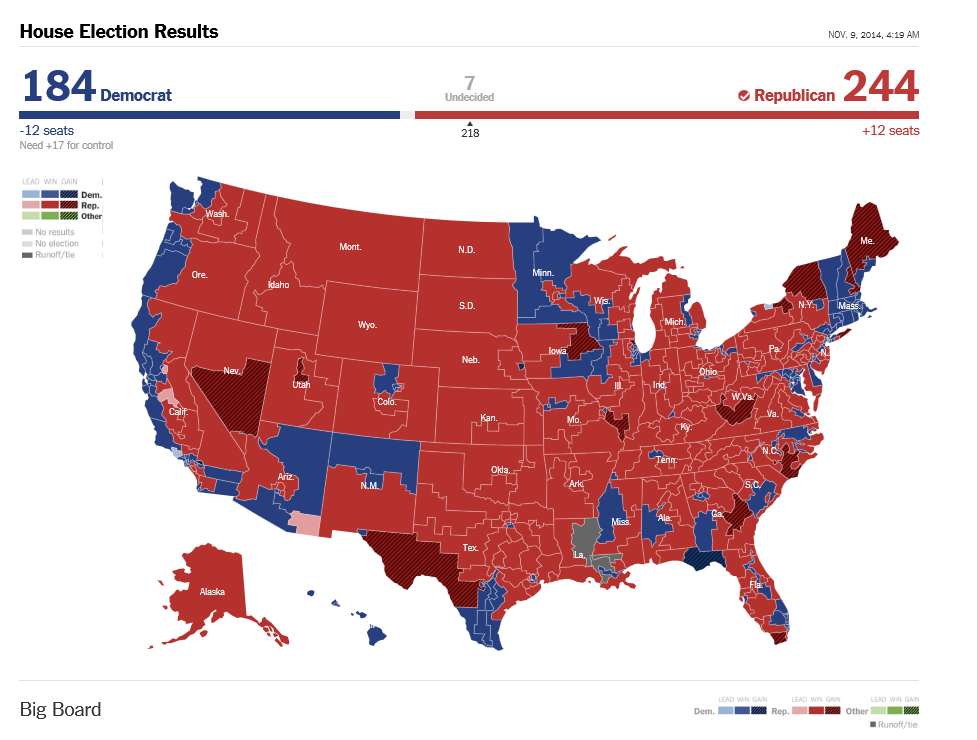

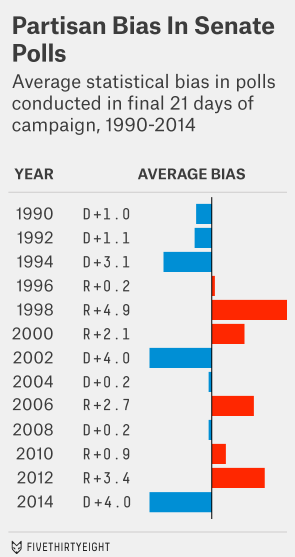

The maxim that gridlock in Washington is good for markets has certainly held true during the “do nothing” Congress of the past two years. Now, with the Republicans winning control of the Senate and adding 15 seats to their House majority, the outlook appears to be for more of the same. Happily for investors, an analysis going back to 1900 shows that equity markets have averaged annualized 15% returns when the Congress is controlled by Republicans and the White House by a Democrat.

Although many pundits have suggested that the GOP sweep creates a mandate, the Global Investment Committee (GIC) sees the results as a mandate for change in the functioning and compromise in Washington rather than the embrace of a specific agenda. On that score, unlike the deeply partisan divide between the House and the Senate of the last four years that prevented any compromise bills from getting off the Hill, legislation may actually get to the president’s desk. While President Obama will be free to veto, he is now playing for his legacy and may be apt to compromise on some issues.

The Republicans’ challenge is to demonstrate leadership and competence in governing, a task that will require corralling the Tea Party caucus and, as Morgan Stanley & Co. Chief US Economist Vincent Reinhart wrote last week, “sequencing priorities” in a constructive way. Lacking a coherent issue-driven platform, most Republicans simply ran against Obama. Party infighting or an immediate battle about the debt ceiling and budget authorizations would likely be disastrous for the GOP—and the markets. From the GIC’s perspective, a better result would be for Congress to focus on job-creating initiatives and not on eviscerating the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

Agreement should be easiest around initiatives involving the energy sector, where this year’s 25% decline in oil prices has been front and center. American energy independence is no longer a dream but a real prospect with profound geopolitical as well as economic consequences (see Chart of the Week, page 3). Heretofore, the Keystone XL pipeline, a six-year-old proposal to connect Canadian oil with US Gulf Coast refineries, has been stalled amid wrangling with environmentalists. We believe the pipeline is now likely to win approval, creating a large national infrastructure project. Similarly, the growth of US energy supply is likely to reignite a debate on oil exports, which have been banned since the Arab oil embargoes of the 1970s. With US dollar strength likely to crimp other exports, expanding energy exports is a way to maintain economic growth. There is likely to be similar debate about exports of liquefied natural gas as the US is the world’s largest and lowest-cost producer. We believe that energy exports would be a major beneficiary focus if the new Congress approves the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a free trade agreement that would give the president authority to negotiate deals with 11 Asian nations.

Beyond energy, we expect repeal of the medical-device tax; expansion of defense spending, which has been curtailed under sequestration; and a debate on corporate tax reform, especially given the noise around tax-driven international mergers. Revisions to the ACA, to the extent they are pursued, will likely focus on measures that impact the number of insured and thus, hospitals and managed-care companies. The employer mandate, which requires employers with more than 100 workers to make available health insurance for any employee working more than 30 hours per week, is most likely to be revised, in our view.

As a final note, a review of state and local ballot initiatives suggest that voters are far from embracing an ideological position on fiscal austerity. Minimum-wage increases were passed in each state where they were on the ballot as did several large new-money infrastructure projects in New York and California—a development that MS & Co. Municipals Strategist, Michael Zezas, notes will likely increase bond supplies in 2015.

It looks like the august Global Economic Forum is being being published more infrequently than in the past, the last edition being March 5 of this year.

Wells Fargo

Wells Fargo, accounting to Wikipedia is –

an American multinational banking and financial services holding company which is headquartered in San Francisco, California, with “hubquarters” throughout the country… It is the fourth largest bank in the U.S. by assets and the largest bank by market capitalization…Wells Fargo is the second largest bank in deposits, home mortgage servicing, and debit cards. In 2011, Wells Fargo was the 23rd largest company in the United States.

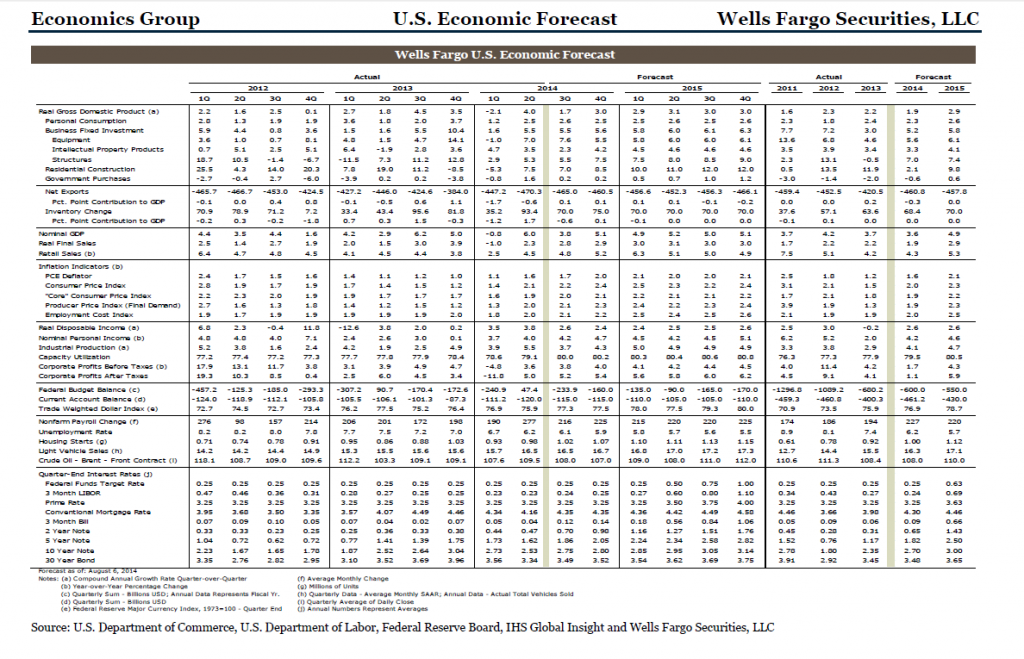

The Wells Fargo website has a suite of forecasting reports, ranging from weekly, to monthly, to the big annual report, all downloadable in PDF format.

In October, the bank also released this video interview about their economic outlook.

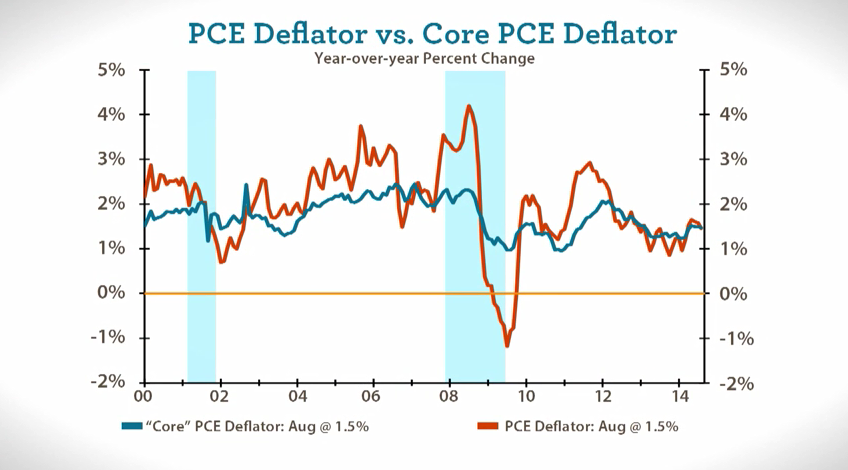

In case you did not get time to watch that, one of the key graphics is the PCE deflator, which has been trending down recently, raising the spectre of deflation in the minds of some.

Credit Agricole

Credit Agricole is an international full services banking company, headquartered in France, with historical ties to French farming,

Their website offers at least two quarterly macroeconomic forecasting publications.

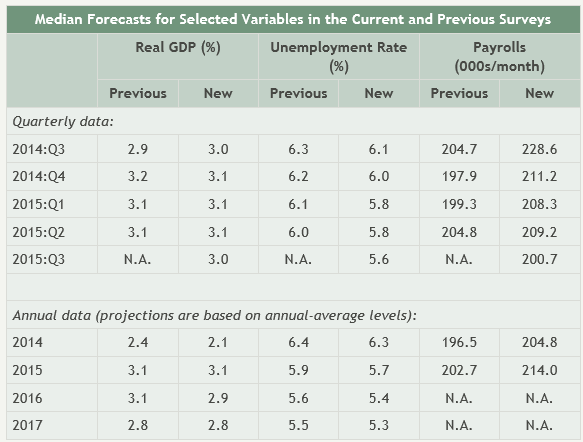

The publication Economic and Financial Forecasts presents a series of tabular forecasts for interest rates, exchange rates and commodity prices, together with the Crédit Agricole Group’s central economic projections. This is a kind of “just the numbers ma’am report.”

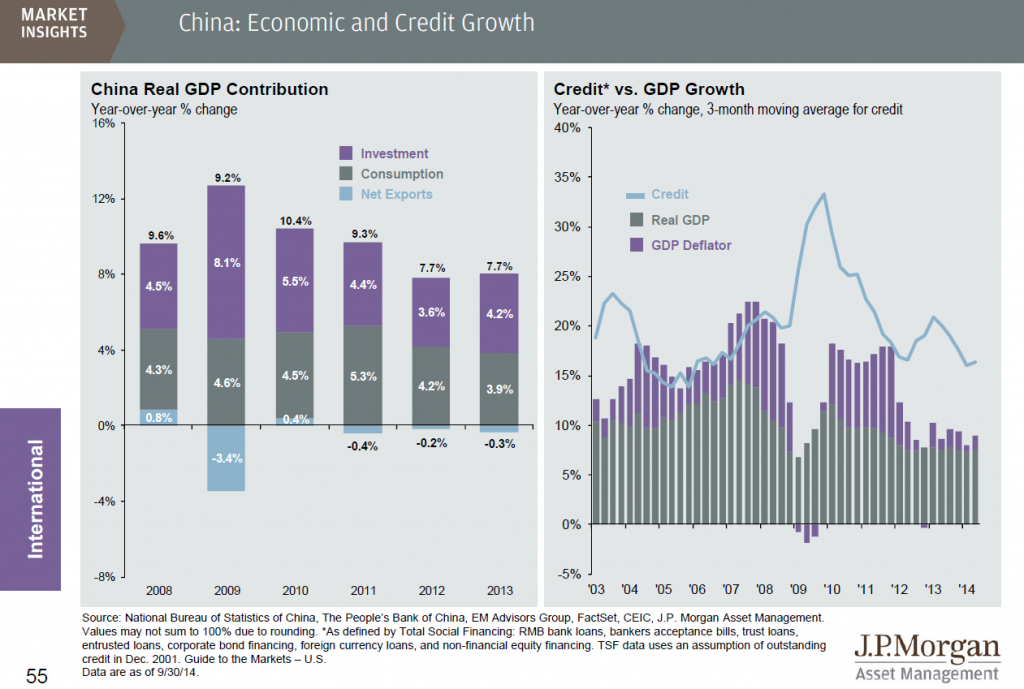

Macro Prospects is more discursive and with short highlights on key countries, such as, in the September issue, Brazil and China.

I signed up for emails from Credit Agricole, announcing updates of these documents.