What are we to make of negative interest rates?

Burton Malkiel (Princeton) writes in the Library of Economics and Liberty that – The rate of interest measures the percentage reward a lender receives for deferring the consumption of resources until a future date. Correspondingly, it measures the price a borrower pays to have resources now.

So, in a topsy-turvy world, negative interest rates might measure the penalty a lender receives for delaying consumption of resources to some future date from a more near-term date, or from now.

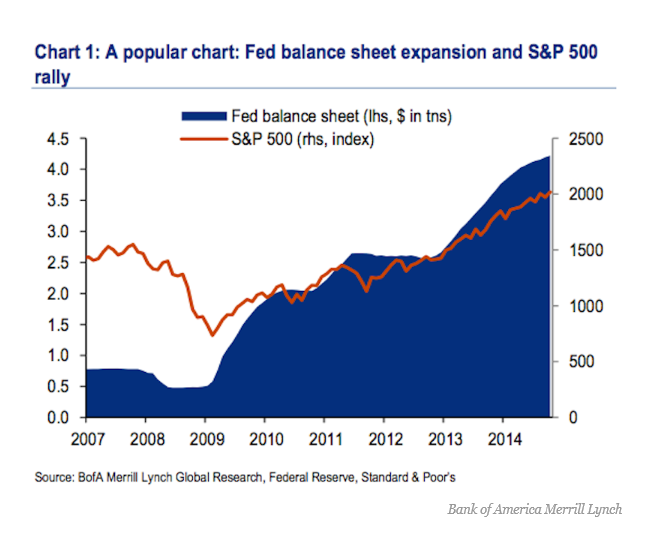

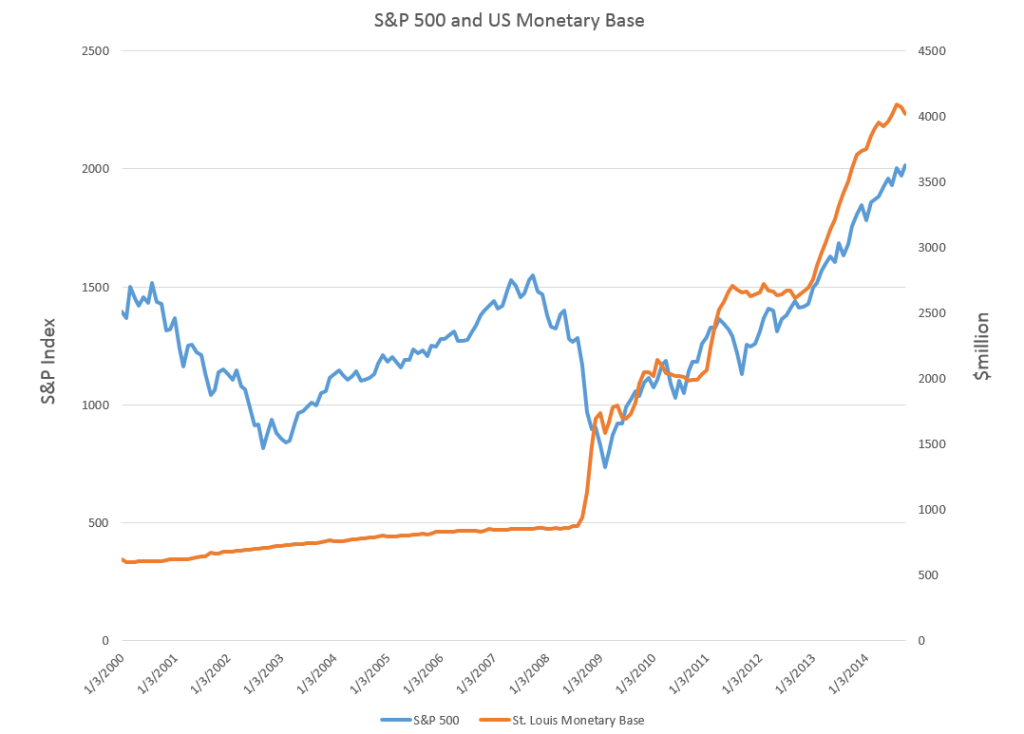

This is more or less the idea of this unconventional monetary policy, now taking hold in the environs of the European and Japanese Central Banks, and possibly spreading sometime soon to your local financial institution. Thus, one of the strange features of business behavior since the Great Recession of 2008-2009 has been the hoarding of cash either in the form of retained corporate earnings or excess bank reserves.

So, in practical terms, a negative interest rate flips the relation between depositors and banks.

With negative interest rates, instead of receiving money on deposits, depositors must pay regular sums, based on the size of their deposits, to keep their money with the bank.

“If rates go negative, consumer deposit rates go to zero and PNC would charge fees on accounts.”

The Bank of Japan, the European Central Bank and several smaller European authorities have ventured into this once-uncharted territory recently.

Bloomberg QuickTake on negative interest rates

The Bank of Japan surprised markets Jan. 29 by adopting a negative interest-rate strategy. The move came 1 1/2 years after the European Central Bank became the first major central bank to venture below zero. With the fallout limited so far, policy makers are more willing to accept sub-zero rates. The ECB cut a key rate further into negative territory Dec. 3, even though President Mario Draghi earlier said it had hit the “lower bound.” It now charges banks 0.3 percent to hold their cash overnight. Sweden also has negative rates, Denmark used them to protect its currency’s peg to the euro and Switzerland moved its deposit rate below zero for the first time since the 1970s. Since central banks provide a benchmark for all borrowing costs, negative rates spread to a range of fixed-income securities. By the end of 2015, about a third of the debt issued by euro zone governments had negative yields. That means investors holding to maturity won’t get all their money back. Banks have been reluctant to pass on negative rates for fear of losing customers, though Julius Baer began to charge large depositors.

These developments have triggered significant criticism and concern in the financial community.

Japan’s Negative Interest Rates Are Even Crazier Than They Sound

The Japanese government got paid to borrow money for a decade for the first time, selling 2.2 trillion yen ($19.5 billion) of the debt at an average yield of minus 0.024 percent on Tuesday…

The central bank buys as much as 12 trillion yen of the nation’s government debt a month…

Life insurance companies, for instance, take in premiums today and invest them to be able to cover their obligations when policyholders eventually die. They price their policies on the assumption of a mid-single-digit positive return on their bond portfolios. Turn that return negative and all of a sudden the world’s life insurers are either unprofitable or insolvent. And that’s a big industry.

Pension funds, meanwhile, operate the same way, taking in and investing contributions against future obligations. Many US pension plans are already borderline broke, and in a NIRP environment they’ll suffer a mass extinction. Again, big industry, many employees, huge potential impact on both Wall Street and Main Street.

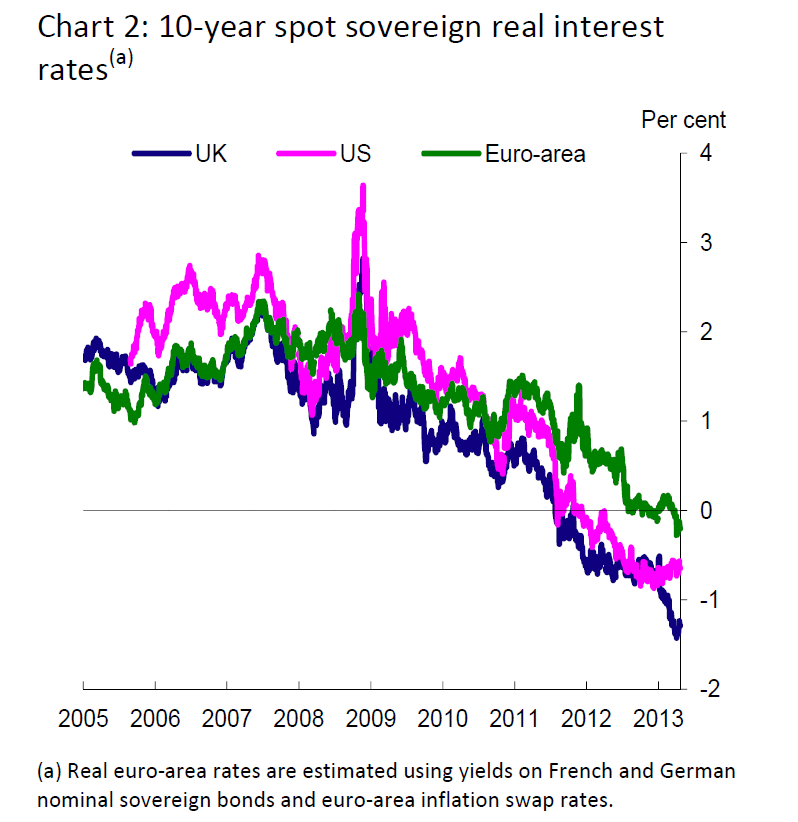

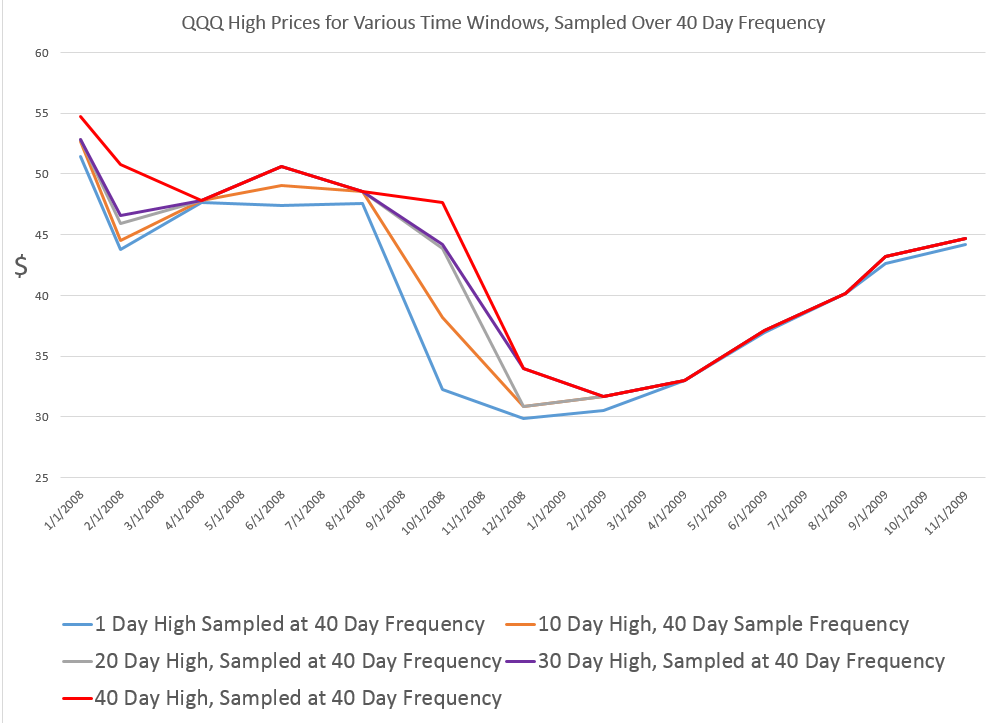

It has to be noted, however, that real (or inflation-adjusted) interest rates have gone below zero already for certain asset classes. Thus, a highlight of the Bank of England Study on negative interest rates circa 2013 is this chart, showing the emergence of negative real interest rates.

Are these developments the canary in the mine?

We really need some theoretical analysis from the economics community – perspectives that encompass developments like the advent of China as a major player in world markets and patterns of debt expansion and servicing in the older industrial nations.