One my focuses is the global economy and any cracks in the firmament which might presage the next recession. I rely a lot on my Twitter account to keep me on the crest of the wave, in this regard.

I’m really concerned, as are many of my colleagues and contacts in business and government.

We’ve hardly escaped the effects of last recession 2008-2009. Those are US dates, of course, set by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) the official recession “dater” in this country.

There have been a series of rolling impacts and consequences of this so-called “Great Recession.”

Europe

Housing or real estate bubbles were present in Europe, too, particularly in Spain and Ireland. Then, there was the problem of the Greek economy and state, which did not support the level of public debt that had been garnered by, in some cases, corrupt public officials. And European problems were complicated by the currency union of the euro in a context where there is not, as yet, a centralized EU state. Anyway, not to reprise the whole matter blow-by-blow, but most of Europe, with the exception of Germany, plunged into recession and struggled with austerity policies that made things worse for Main Street or, as they like to say in Britain, “High Street.”

Many European countries are just now coming out of recession, and overall, the growth rate in the EU area is almost indistinguishable from zero.

So another recession in the next one to two years would really set them back.

China

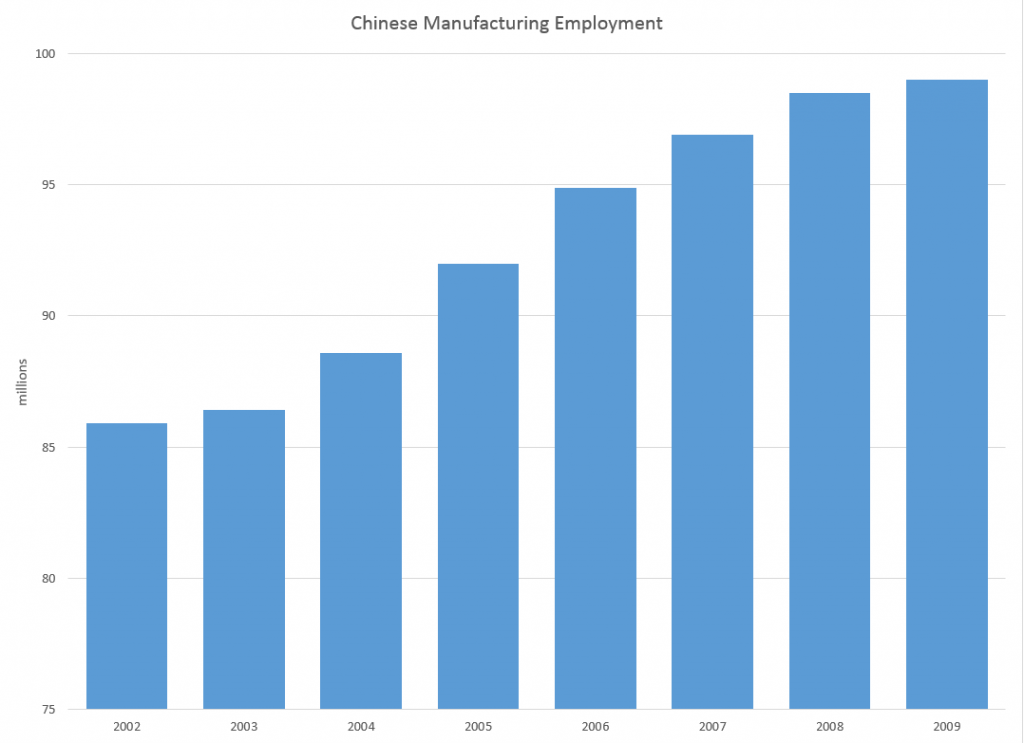

Part of the problem China has been experiencing is related to the persisting downturn in most of Europe, since Europe is a big trading partner. And so, for that matter is the United States, which bought less from China during the recession years.

But another problem is that China now is experiencing a mojo big property bubble of its own.

Newly wealthy Chinese do not really have any place to put their money, except real estate. The Chinese, like the Japanese, are big savers, and for many middle class families, buying the second apartment or even a house is an investment for the future. Yet Chinese real estate prices have skyrocketed, leaving the average Chinese wage earner in the dust, with less and less hope of ever owning a residence.

Apparently, in connection with this real estate speculation, a large shadow banking system has emerged. Some estimates circulate on Twitter suggesting this rivals the size of the official Chinese banking system.

Can “market socialism” or “market Leninism” experience a financial crisis, based on too many debts that cannot be paid?

I’ve been to China a few times, and done some business there – all the while trying to understand how things are set up. My feeling is that one should not impute banking practices that seem pro forma in, say, Great Britain or the US, to the Chinese. I think they are much more ready to “break the rules” in order to keep the party going (which is sort of a pun).

Having said that, I do think a Chinese crisis could develop if property values collapse, as they are wont to do in bubble mode.

Again, it’s hard to say how this might play out, since the victims and suffering would be among the nouveau riche of China, of whom there are millions, and many more average families who have invested their nest egg in a hot property.

But I can’t think that collapse of real estate values in modern China would not have worldwide repurcussions.

The Rest of the World

Regrettably, I cannot go through other major regions, one-by-one, but I’d have to say that things are not so good. The BRIC’s as a group all have more problems than a few years back, when they were hailed as the bright new centers of economic growth by that Goldman Sachs analyst. That’s Brazil, Russia, India, and China, of course.

Possibilities of Increased Conflict

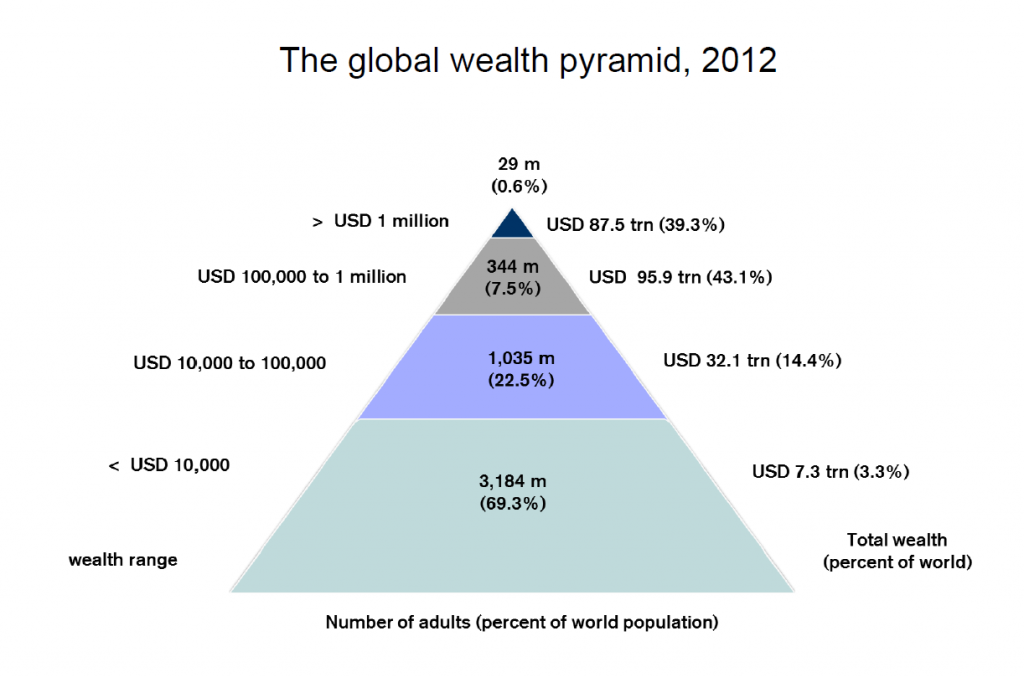

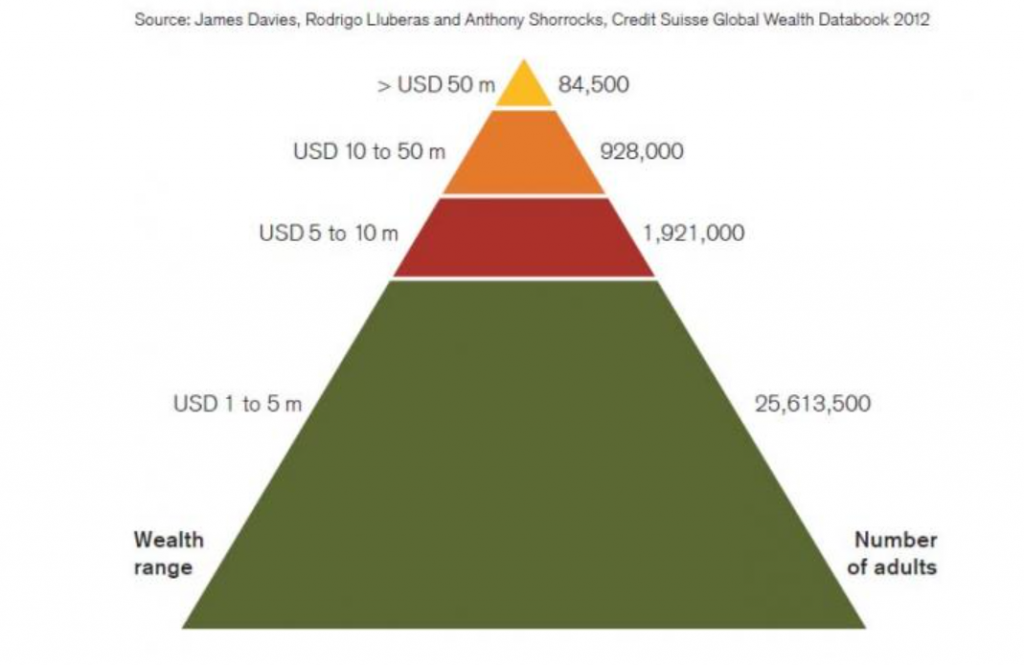

There is a kind of axiom of geopolitics and social interaction that when the pie is growing and everybody can get more, even though their slice may not have been very big to begin with, there is a tendency for people to make do, go about their business and so forth. Reverse this and you have the concept that shrinking the pie – as austerity policies and the Great Recession have done – tends to increase levels of conflict. At first, to the extent that people have the idea that “we are all in this together” there may be increased cooperation. But that is not the current situation in almost any society. Quite the contrary, as Piketty and the Occupy Movement highlight, there is growing awareness of inequality of wealth and income.

There are armed conflicts in Syria, the Ukraine, Afghanistan (resurgent Taliban), and areas and regions in Africa. The Indian elections recently installed a Hindu nationalist who hopefully will be a reformer, but may, if the going gets tough, revert or acquiesce to more conflict with Pakistan and with non-Hindu populations within India. Pakistan, one of the world’s nuclear powers, appears to be extremely unstable politically. There are deep civil divisions in Thailand between city and rural areas that parallel class divisions. China is flexing its muscles in the South China Sea.

And we may be moving from an era of US-centric global capitalism to a time when the Eurasian supercontinent will become significantly more important and perhaps decoupled from Wall Street and the City of London. Already, there are threats to dollar supremacy, and, historically, as US economic power is eclipsed by the more rapidly growing economies of Asia, some adjustment seems predictable.

In all this, Hollywood can be counted on to roll out some really corking new international intrigue films, perhaps (although I doubt it) with more complex plots.

The Situation with the US Federal Reserve Bank

The point of this international survey and reprise of recent business history is to highlight areas where surprises may originate, shaking the markets, and perhaps triggering the next recession.

But the most likely suspect is the US Federal Reserve Bank.

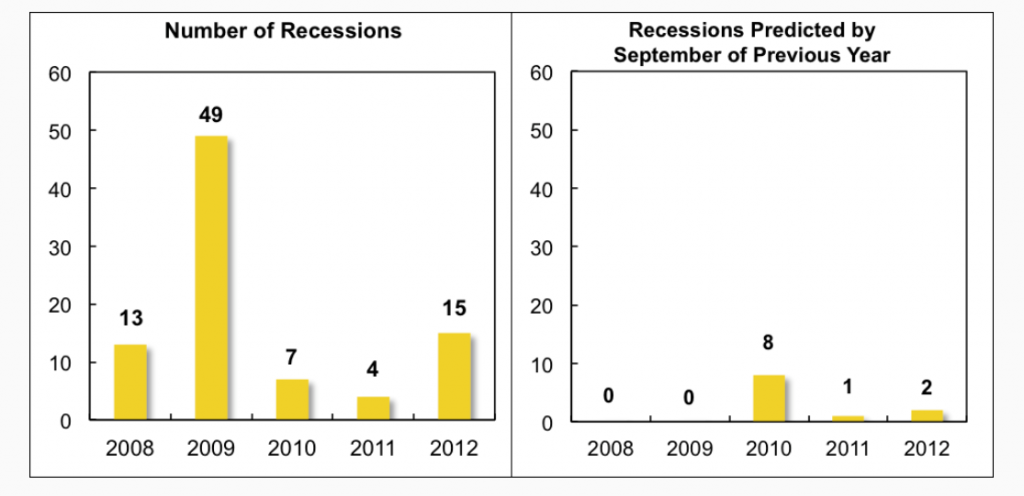

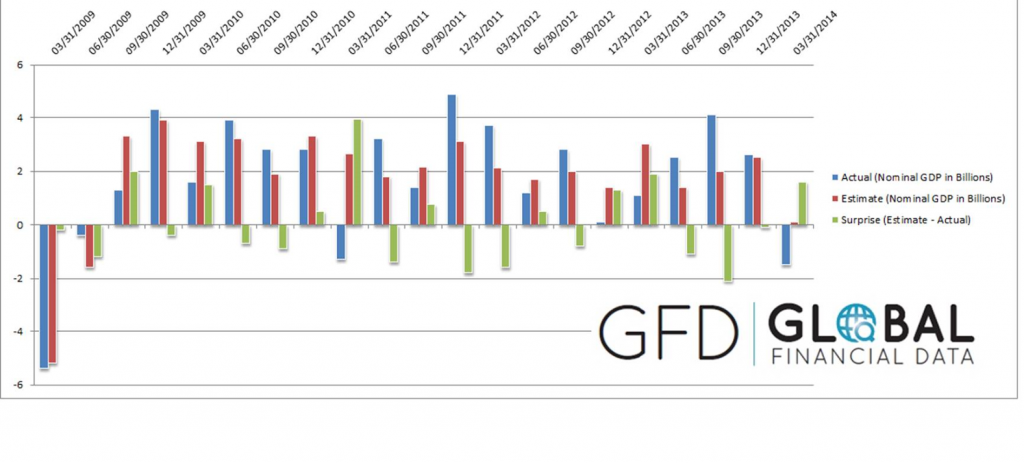

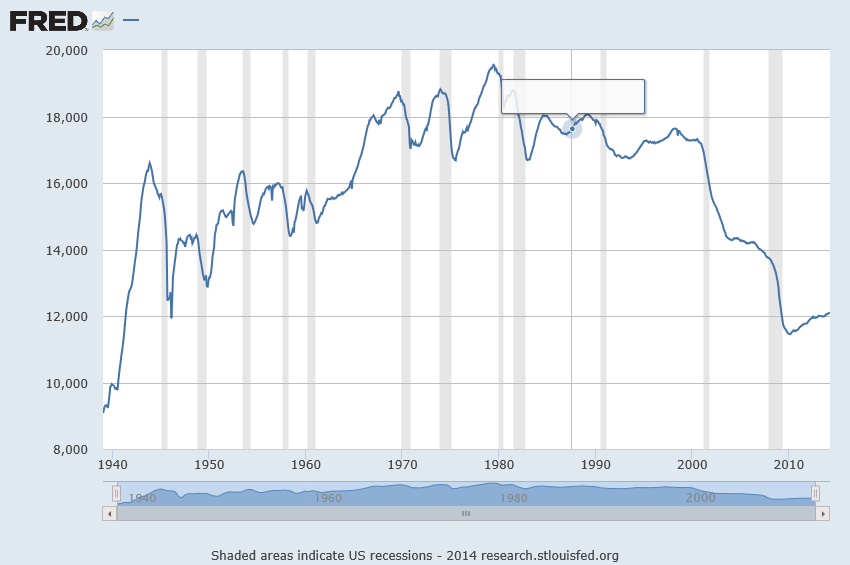

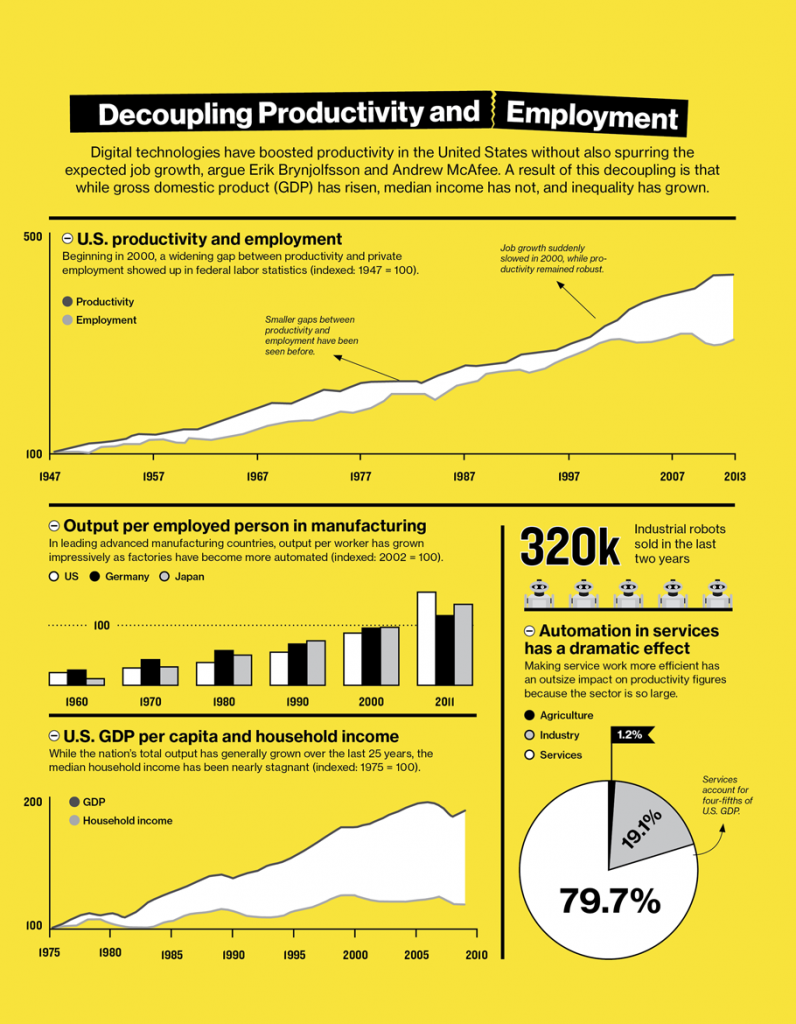

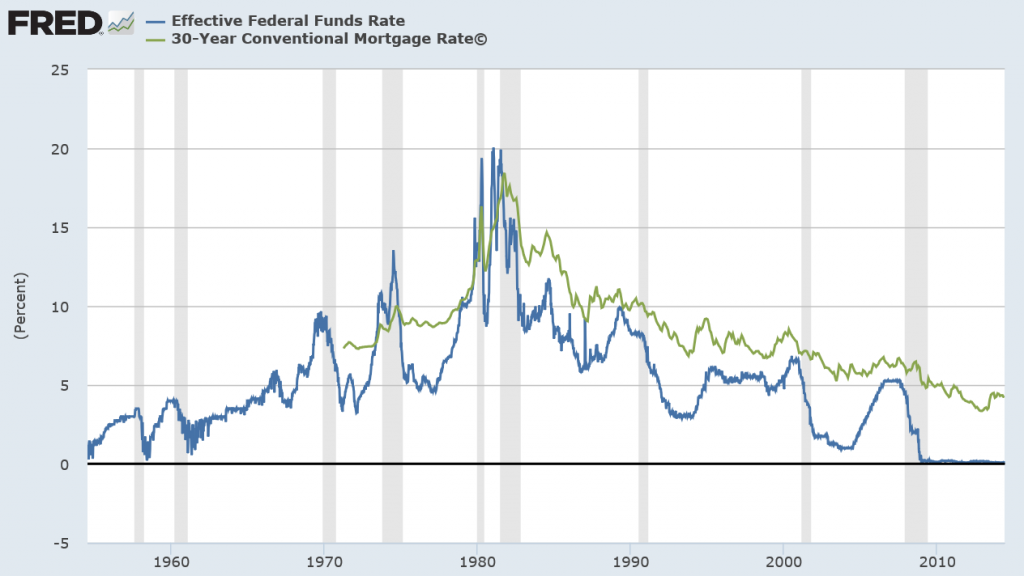

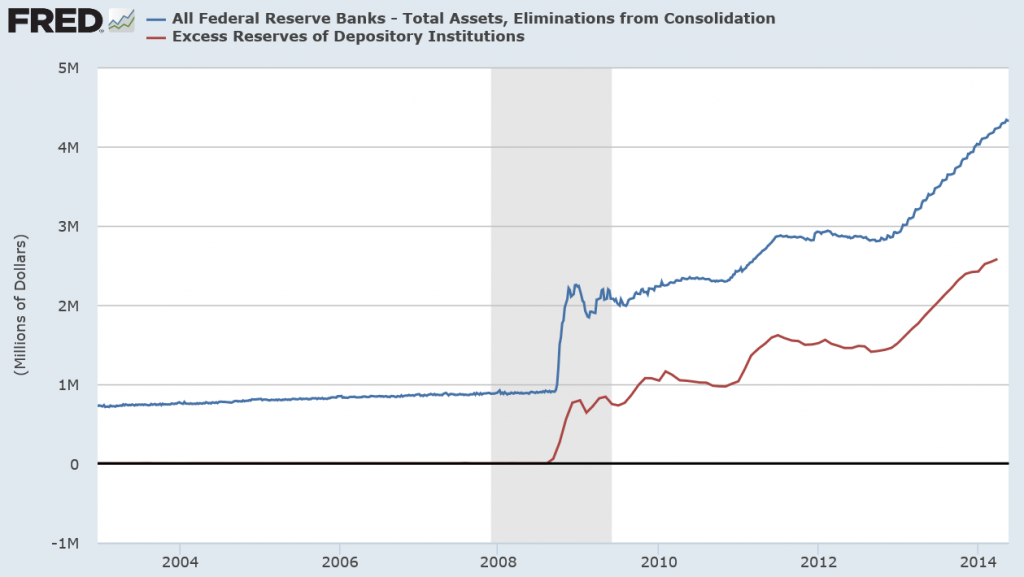

Two graphs speak volumes.

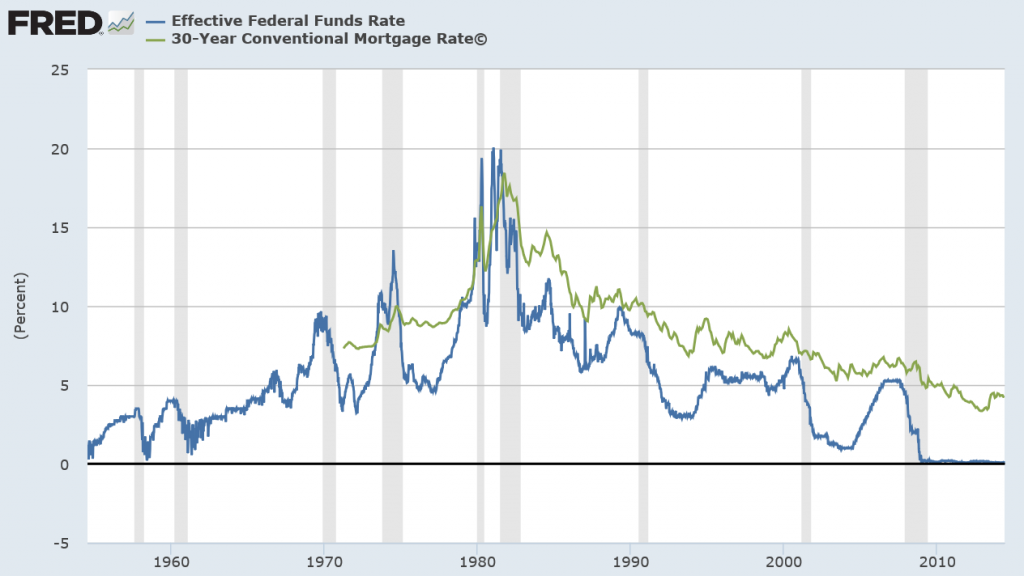

Seeking to encourage economic recovery, the US Federal Reserve dropped the federal funds rate to a number effectively almost zero – a historically low number. This zero bound federal funds rate has persisted since the end of 2009, or for about five years.

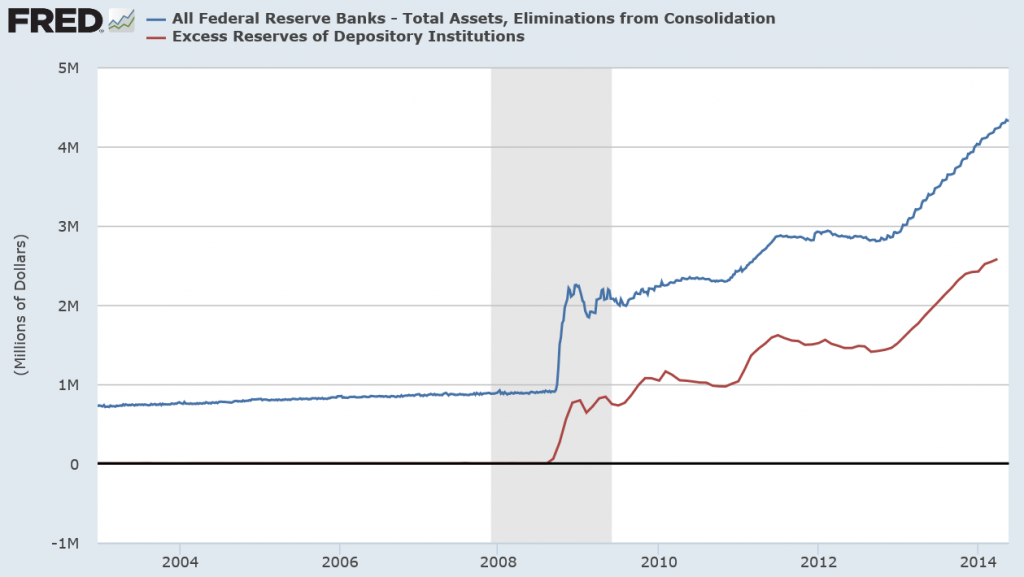

The Fed also has engaged in new policies, whereby it goes into private bond markets and buys long term bonds – primarily mortgage-backed securities. The second chart tracks this inasmuch as a good portion of the more than 4 trillion in Fed assets (for which there are corresponding liabilities, of course) are these mortgage-backed securities. In effect, the Fed has purchased a sizeable portion of the US housing market – one might say “nationalize” except that would be forgetting the fact that the Fed is actually a private institution whose governance is appointed by the Executive Branch of the US government.

In any case, this bond-buying is the famous “quantitative easing” (QE) and is mirrored in the accumulation of excess reserves by the banking system. Generally, that is, banks and financial institutions issue mortgages, sell them among themselves to be packaged in mortgage-backed securities, and the Fed has been buying these.

Banks can easily loan these excess reserves, but they consistently have not. Why is an interesting question beyond the scope of this discussion, but the consequence is that the Fed’s actions are “firewalled” from increasing the rate of inflation, which is what ordinarily you might think would occur given that various metrics of money supply also have surged upward.

Now “Fed-watching” is its own little cottage industry among financial commentators, and I am not going to second-guess the media here. The Fed has announced a plan to “taper” these purchases of long term bonds. This is likely to increase the mortgage rates and, probably to some extent, based on expectations already has.

So, the long and the short of it are that this set of policies – zero federal funds rate and bond buying cannot go on forever.

If economic growth has been low-grade since 2010 with these low interest rates, what is the reasonable outlook for a higher interest rate regime?

Timing of the Next Recession

When is the most likely time for a recession, for example? Would it be later in 2014, in 2015, or thereafter, maybe in 2016.

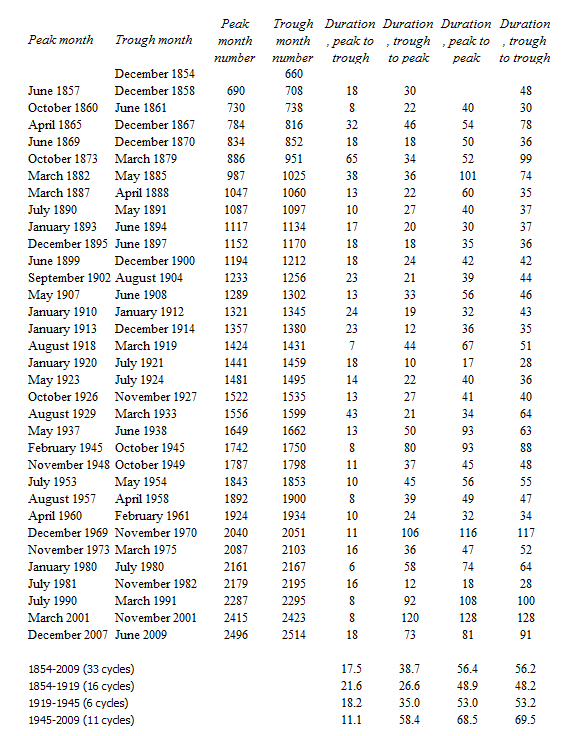

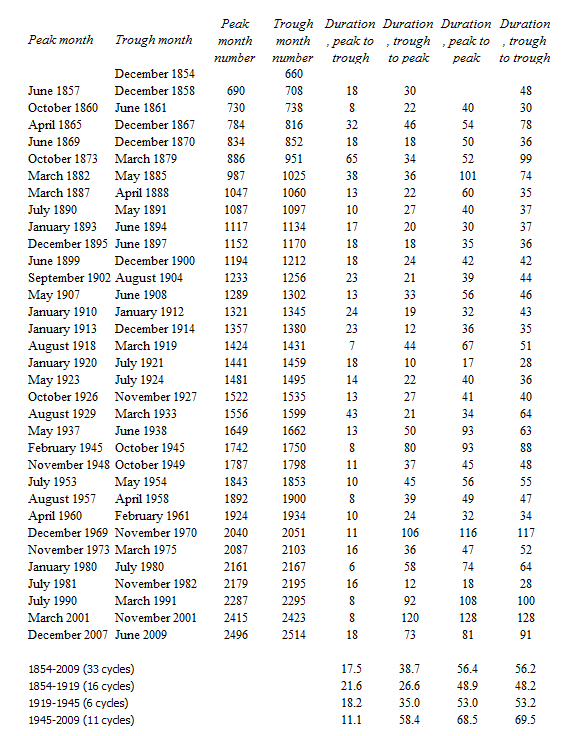

Here is a table of all the recessions in the US since the middle 1850’s along with facts about their duration (source: NBER).

Without even considering averages, the maximum period of trough to trough – that is, from the bottom of one recession to the bottom of the next – has been 128 months or ten years and eight months. Here, incidentally, the month numbers begin January 1800, for what that’s worth.

Thus, at the outside, based on these empirics, the trough of the next recession is likely to occur no later than early 2020.

Note that we have already blown through the average length from trough to trough of about 58.4 months or about five years from June 2009.

On a simple probabilistic basis, therefore, we are moving into the tail of the distribution of business cycle durations, suggesting that the chances of a downturn are in some sense already above 50 percent.

And note that the experience of the current business recovery is nothing like this historically maximum span in the 1990’s between the trough of the recession of 1990-1991 and the trough of November 2001.

This business recovery persistently seems to move ahead just above or, in the last quarter of 2013, below “stall speed.”

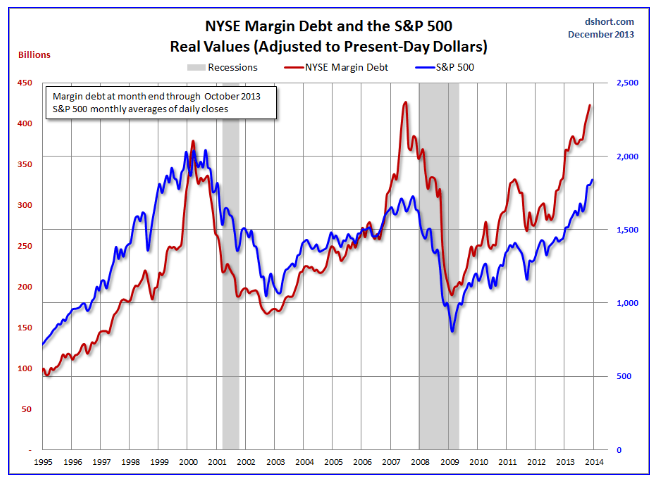

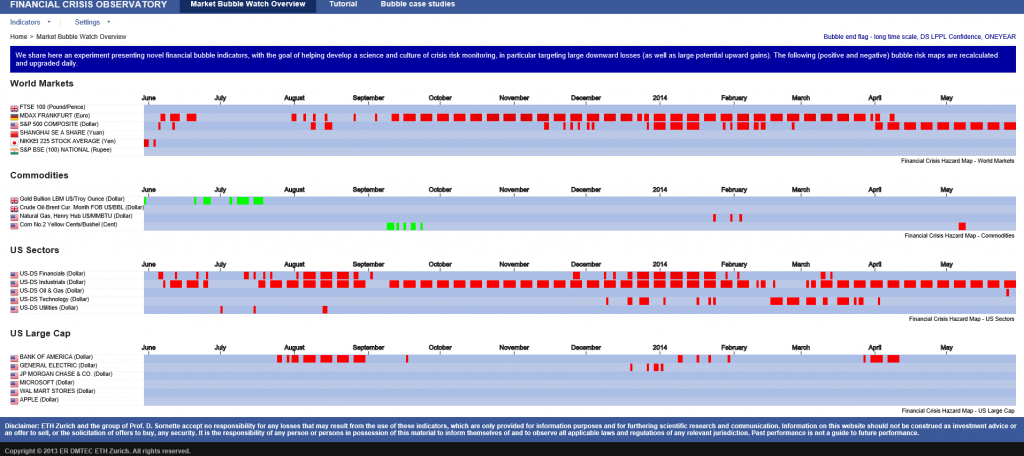

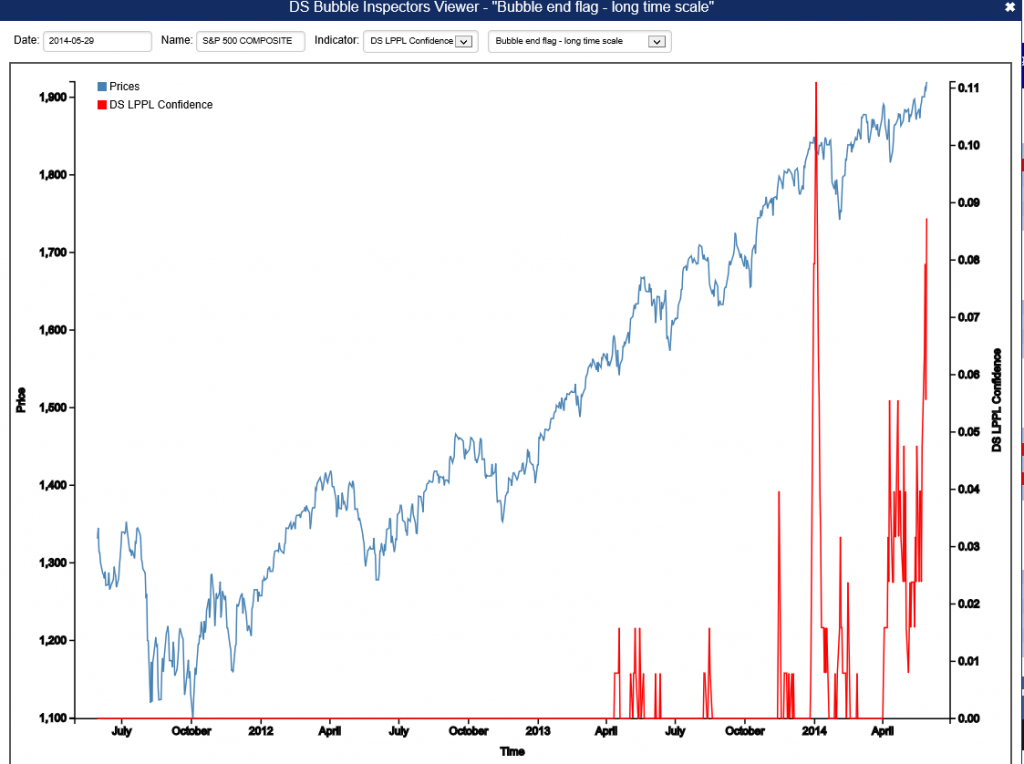

Seemingly, a fairly minor perturbation could set off a chain reaction, given the advanced frothiness in the stock market and softness in housing prices.

More of the Same, Worse

Neil Baroifsky was special inspector with oversight authority for the TARP during the bailout phase of the Great Recession, and currently is a partner in the Litigation Department of national law firm Jenner & Block LLP.

He’s also an author and often is called on for his opinion about developments in malfeasance writ large among the finance giants – such as the Credit Suisse settlement. In connection with a recent NPR interview, Barofsky said,

Although it is good that we averted a catastrophe back in 2008, the way that we did so I believe has unfortunately set the stage for an even more devastating financial crisis in the future.

HOBSON: In the future? How far?

BAROFSKY: Well, if I knew that, Michael Lewis would be writing his next book about people who made billions on timing the markets perfectly about me, which would be great.

(LAUGHTER)

BAROFSKY: But if you look, a lot of the same broken incentives from 2008 are still there. It’s just a question of when, not if. You can’t look at the fundamental broken incentives in the financial system and really come to a conclusion other than that we’re headed down the same dangerous path that we were that culminated in the explosion of ’08.

Barofsky’s point is readily supported by facts, such as –

The US and global financial system is even more concentrated today than in 2007, making “too big to fail”and even bigger potential problem now, than before the Great Recession. Even Alan Greenspan has taken note.

And the “pass the buck” system, whereby bond rating agencies are paid by the originators to evaluate exotic securities (“financial innovations”) created by the banking and shadow banking industries, securities which are then passed on to pension funds and hapless investors – this system appears to still be completely in place. Talk about the concept of “moral hazard.”

Global Impact

I think you get the picture.

For one reason or another, some fairly minor event is likely to set off a cascade of consequences in US and global financial markets, leading to the next recession. Probably, within one, two, or three years, as a matter of fact. Because the US Fed, and, for that matter, other central banks will still be working their way out of the last recession, there may be fewer “policy tools” to halt the stampede to sell, cutback, and so forth. Governments could respond with aggressive fiscal policy, but that option appears limited unless there are major changes in the political climate in the US and Europe.

Personally, I think wholly new directions of policy should be contemplated at the personal, local, regional, and of course at national levels.

We need to create what I have started to call “islands of stability.” This is the old idea of local self-reliance, but in new packaging. I really think there should be discussions widely across the US at least about how to decouple from the global economy and, indeed, from the financial concentrations on Wall Street. As a matter of self-preservation, until such time as more courageous national policies can be undertaken to reign in such obvious risks.