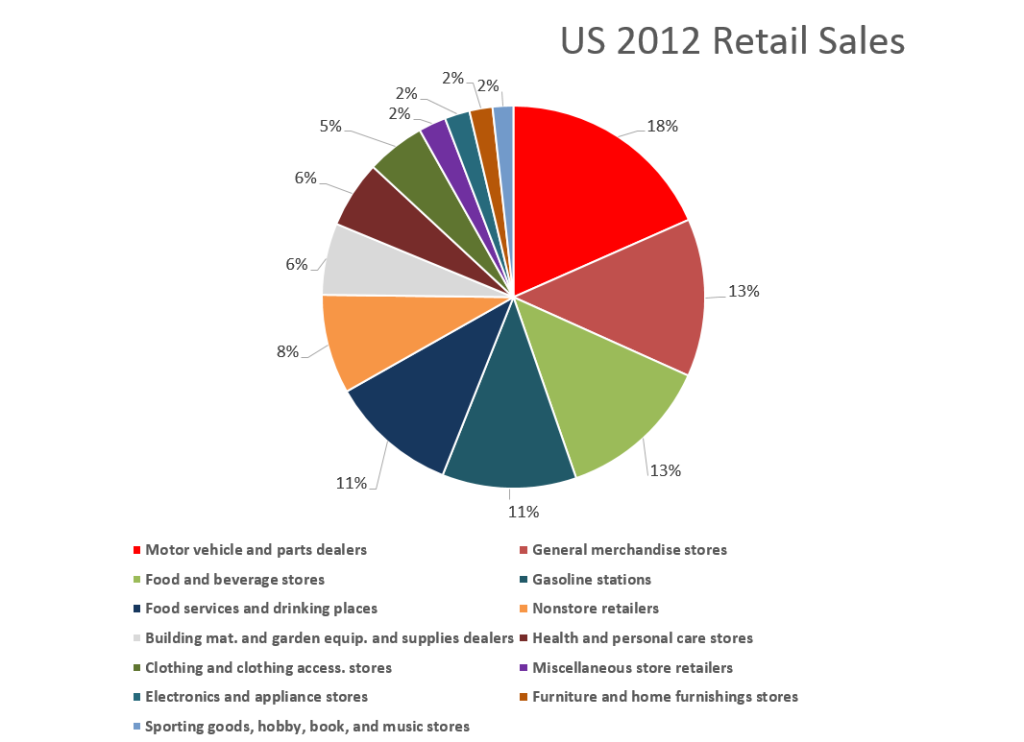

Between one fifth and one sixth of all spending in the US economy, measured by the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), is for health care – and the ratio is projected to rise.

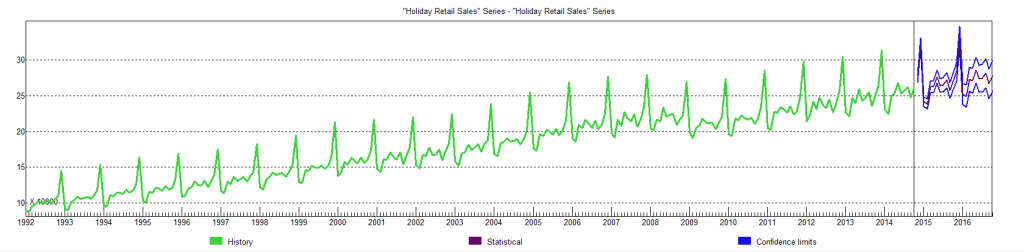

From a forecasting standpoint, an interesting thing about this spending is that it can be forecast in the aggregate on a 1, 2 and 3 year ahead basis with a fair degree of accuracy.

This is because growth in disposable personal income (DPI) is a leading indicator of private personal healthcare spending – which comprises the lion’s share of total healthcare spending.

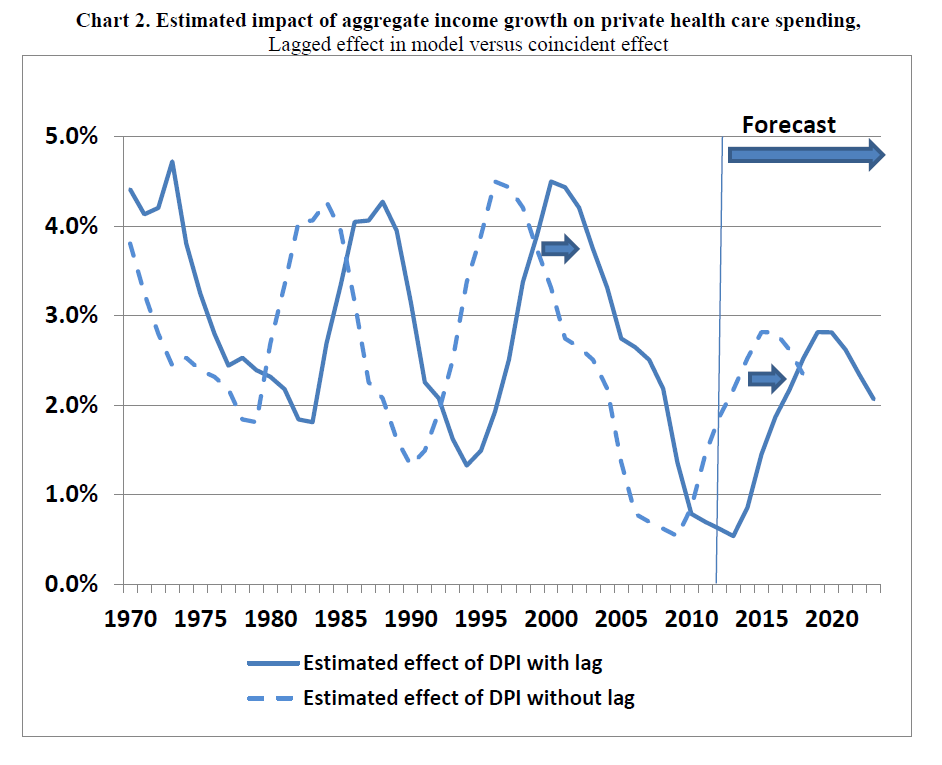

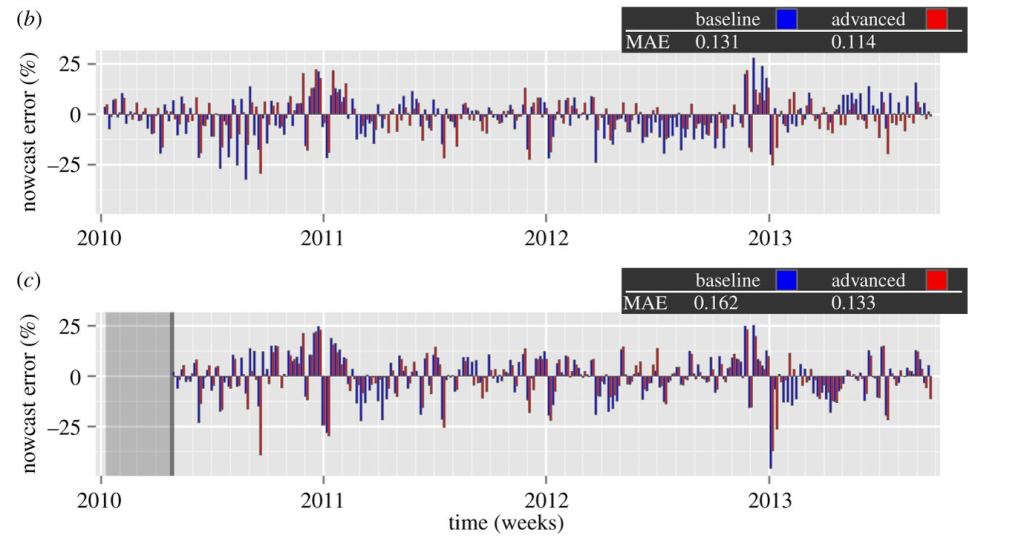

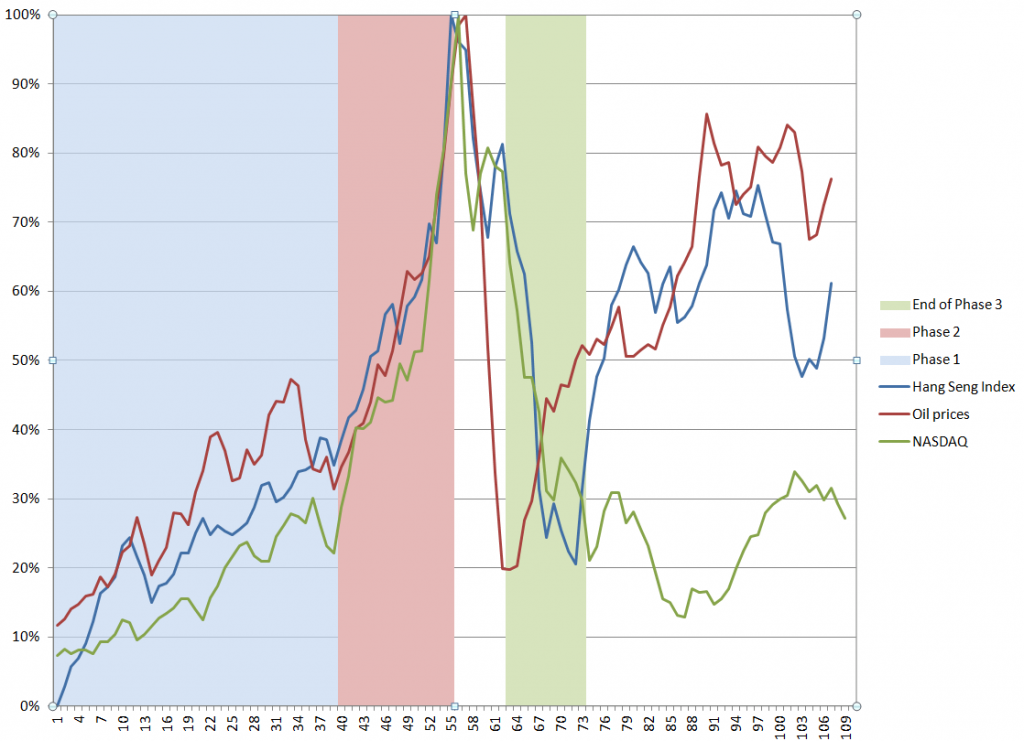

Here is a chart from PROJECTIONS OF NATIONAL HEALTH EXPENDITURES: METHODOLOGY AND MODEL SPECIFICATION highlighting the lagged relationship and private health care spending.

Thus, the impact of the recession of 2008-2009 on disposable personal income has resulted in relatively low increases in private healthcare spending until quite recently. (Note here, too, that the above curves are smoothed by taking centered moving averages.)

The economic recovery, however, is about to exert an impact on overall healthcare spending – with the effects of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) aka Obamacare being a wild card.

A couple of news articles signal this, the first from the Washington Post and the second from the New Republic.

The end of health care’s historic spending slowdown is near

The historic slowdown in health-care spending has been one of the biggest economic stories in recent years — but it looks like that is soon coming to an end.

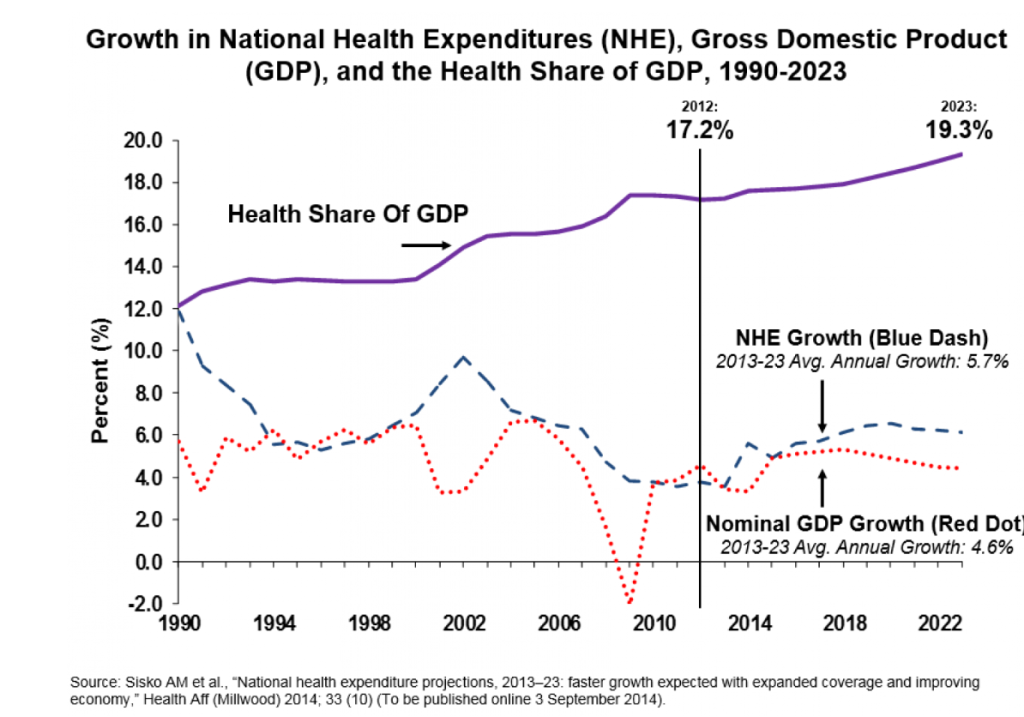

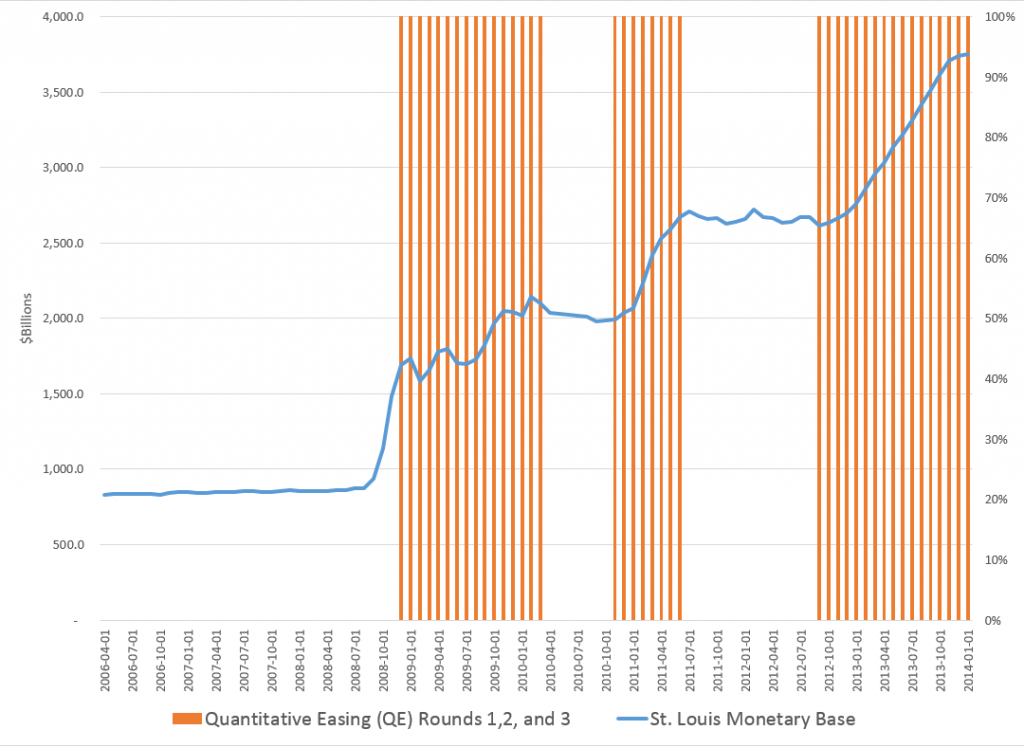

As the economy recovers, Obamacare expands coverage and baby boomers join Medicare in droves, the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ actuary now projects that health spending will grow on average 5.7 percent each year through 2023, which is 1.1 percentage points greater than the expected rise in GDP over the same period. Health care’s share of GDP over that time will rise from 17.2 percent now to 19.3 percent in 2023, or about $5.2 trillion, as the following chart shows.

America’s Medical Bill Didn’t Spike Last Year

The questions are by how much health care spending will accelerate—and about that, nobody can be sure. The optimistic case is that the slowdown in health care spending isn’t entirely the product of a slow economy. Another possible factor could be changes in the health care market—in particular, the increasing use of plans with high out-of-pocket costs, which discourage people from getting health care services they might not need. Yet another could be the influence of the Affordable Care Act—which reduced what Medicare pays for services while introducing tax and spending modifications designed to bring down the price of care.

There seems to be some wishful thinking on this subject in the media.

Betting against the lagged income effect is not advisable, however, as an analysis of the accuracy of past projections of Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) shows.